Critical Thinking

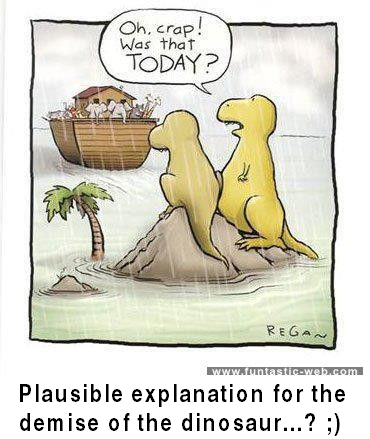

Plausible Explanations

When we come across evidence of an unusual nature, we feel obliged to offer an explanation for our findings - or at least to accept that, when a convincing one is not forthcoming, that one should be provided.

When we come across evidence of an unusual nature, we feel obliged to offer an explanation for our findings - or at least to accept that, when a convincing one is not forthcoming, that one should be provided.Weeping Madonna of Syracuse, Sicily, 1953

The [Madonna] was purchased as a wedding gift for Antonina and Angelo Iannuso, who were married March 21, 1953. They admitted that they were tepid and neglectful Christians, yet they hung the image with some devotion on the wall behind their bed.

Angelo was a laborer who had taken his bride to live in the home of his brother on Via Degli Orti. When his wife discovered that she was pregnant, her condition was accompanied by toxemia that expressed itself in convulsions that at times brought on temporary blindness. At three in the morning on Saturday, August 29, 1953, Antonina suffered a seizure that left her blind. At about 8:30, her sight was restored. In Antonina’s own words:

I opened my eyes and stared at the image of the Madonna above the bedhead. To my great amazement I saw that the effigy was weeping. I called my sister-in-law Grazie and my aunt, Antonina Sgarlata, who came to my side, showing them the tears. At first they thought it was a hallucination due to my illness, but when I insisted, they went close up to the plaque and could well see that tears were really falling from the eyes of the Madonna, and that some tears ran down her cheeks onto the bedhead. Taken by fright they took it out the front door, calling the neighbors, and they too confirmed the phenomenon…

(Source: www.visionsofjesuschrist.com)

When we come across evidence of an unusual nature, such as the above, we feel obliged to offer an explanation for our findings - or at least to accept that, when a convincing one is not forthcoming, that one should be provided. Contrast the view that the Madonna’s tears are miraculous:

When we come across evidence of an unusual nature, such as the above, we feel obliged to offer an explanation for our findings - or at least to accept that, when a convincing one is not forthcoming, that one should be provided. Contrast the view that the Madonna’s tears are miraculous:

“The Blessed Mother’s tears are part of her signs. Her tears testify to the fact that there is a Mother in the Church and in the world. . . These tears are also tears of prayers. They are the tears of the Mother’s prayers, which give strength to all others’ prayers and are offered up as an entreaty for all those who are preoccupied with numerous other interests and, thus, are refusing to lend their ears to the calls from God, and are not praying.

(John Paul II [1994])

with that of Chemistry researcher, Dr. Luigi Garlaschelli:

The secret … is to use a hollow statue made of thin plaster. If it is coated with an impermeable glazing and water poured into the hollow centre from a tiny hole in the head, the statue behaves quite normally.

The plaster absorbs the liquid but the glazing prevents it from pouring out. But if barely perceptible scratches are made in the glazing over the eyes, droplets of water appear as if by divine intervention - rather than by capillary attraction, the movement of water through sponge-like material.

(The Independent: Science debunks Miracle)

Why do we find ourselves naturally sympathising with the latter, when neither response has effectively been proved (the effigy itself lies safely secured behind a glass panel)? The answer here is of course, simple. In the absence of proof, we settle for plausibility.

But what is meant by plausible? Reponses to this question tend to be question-begging. We might, for example, say that a plausible explanation isn’t too ‘farfetched’ or ‘fanciful’ or that it offers a ‘tenable’ hypothesis (see Claims). But here we are in danger of circularity (see begging the question, circularity argument in fallacies) – because what we are really saying boils down to: ‘a plausible explanation is one that is plausible!’

However, in daily life, we use the term for just those occasions where we are convinced of something (e.g. an alibi or an excuse) despite there being insufficient evidence for it to count as a proof. We nonetheless accept it until a rival explanation comes along to equal or upstage it.