Plagiarism

Avoid Plagiarism with... Summarising

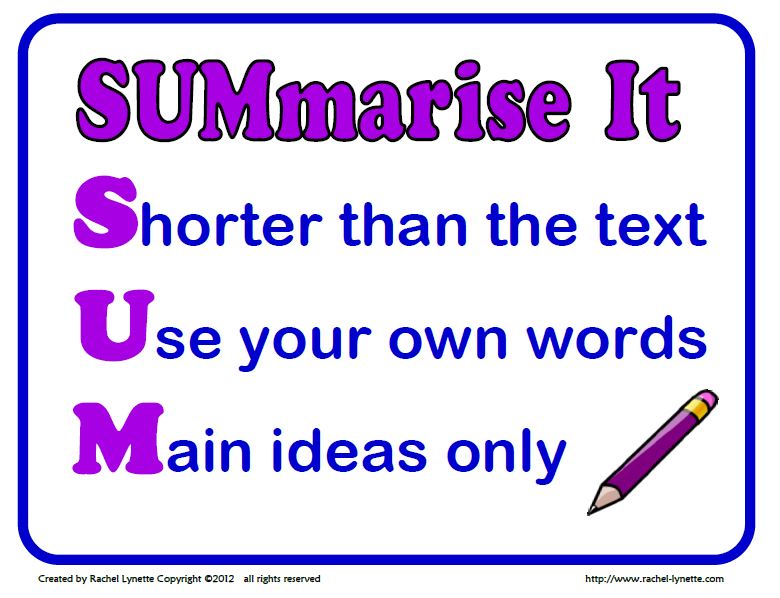

Summarising involves condensing (reducing) a writer’s ideas into their essence using your own words when you want to briefly discuss an extended section of a text. Summaries may vary in length, but are rarely more than twenty percent of the length of the original text.

Summaries also include abstracts, but abstracts are a different style of writing (speak to your EPQ mentor or your subject teacher if you need to complete one of these)

XXX

How to sumarise

1. Read the section of text you want to use straight through from beginning to end. Look up unfamiliar words. Make sure you understand what you are reading. You cannot translate information you do not understand.

2. Minimize the screen or turn the text over. Without looking back at the original, write down a brief description of your understanding of the text. Do not peek back at the text as you do this, as this will force you to use your own words.

XXX

3. Read the original text a second time to check how accurately you have interpreted it in your own rewording. Your new sentences will become the essence of your summary.

4. Using your new sentences, write a first draft of your summary.

5. Begin your summary with the original writer’s name, for example you might write: According to Deford (2000),....

6. Check your draft against the original source:

- Have you accurately communicated the main idea and supporting points?

XXX - Have you followed the same order or sequence of ideas that the original writer used?

XXX - Have you discussed the author’s most important concepts or terms in your own words?

XXX - Would your summary make sense to a reader other than yourself, especially one who has not read the original source but wants to understand what it says?

7. Revise and recheck against the original. Record the page number(s) in case you need them later.

Remember, a summary should be at most 20% of the original length of the text - if your summary is just as long or longer, it is not a summary!

An example of Summarising:

|

Original text from the Journal of Sport Management: One of the most contentious debates surrounding the indirect effects of athletics concerns its impact upon non-athletic gifts to universities. The major improvements of programs at Northwestern in 1995 and Georgia Tech in 1991 prompted speculation and some anecdotal evidence supporting the argument that athletic success contributes to additional general giving. However, this evidence and the proposition behind it has often met strong rebuttal. The reasons behind the challenges are easy to understand; the likely impacts of athletics on general giving are much harder to unambiguously assess than are the types of effects we have discussed to date (athletic department revenues and expenses, media coverage). Moreover, the cause-effect relationships can be quite ambiguous. Some benefactors are interested in both athletics and general university welfare but have a fixed amount of money they are willing to donate. In such cases, increased athletic success may help steer these donors toward athletic giving and away from general gifts. On the other hand, greater exposure for a university, whatever its source, may help spur giving across many fronts. The effect that is expected to dominate (athletic vs. general giving) cannot be theoretically determined. Comparisons across empirical studies are complicated by the use of different dependent variables, use of different variables to account for athletic success, different control variables, and a lack of investigation of lag relationships. For example, Baade and Sundberg (1996) try to explain gifts per alumni for 167 schools over an eighteen-year period, Grimes and Chressanthis (1994) consider annual gifts for one school over a thirty-year time frame, and McCormick and Tinsley (1990) estimate the relationship between athletic gifts and general giving. Even if effects are determined using comparable methods for different institutions, the answer as to whether athletic success and athletic giving reduce or increase general giving may depend on the specific university in question as well as the specific circumstances surrounding its athletic success (e.g., how "big" and how novel the success was.). Goff, Brian. "Effects Of University Athletics On The University: A Review And Extension Of Empirical Assessment." Journal Of Sport Management 14.2 (2000): 85. SPORTDiscus with Full Text. Web. 27 June 2014. |

Sample Summary:

According to Goff (2000), there is no conclusive evidence about the relationship between athletic success and general donations to universities. Athletic success increases a university‘s exposure, which may attract general gifts, or may instead increase donations only to athletics, to the detriment of other areas. Determining the effect athletic success has on general giving has proved to be challenging and occasionally controversial. Goff explains there is no consistent method for studying this phenomenon, and that the unique variables at different schools further complicate the results of any study.

Quick activities you can now do to practice this skill:

Quick activities you can now do to practice this skill:

1. Try using the Summarising Pyramids from the note-taking module of the Core Study Skills course and upload an example.

2. Read through this PowerPoint on summarising and practice the nursery rhyme summaries at the end to see how well you do.

XXX

XXX

This page is reworked from: http://www.wcu.edu/WebFiles/PDFs/Avoiding-Plagiarism-2014.pdf