Research Skills

| Site: | Godalming Online |

| Course: | Study Skills |

| Book: | Research Skills |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Monday, 23 December 2024, 12:10 AM |

Introduction

You've probably already guessed that knowledge doesn't magically appear in books or on websites. In those cases (or, at least, for the more reliable books and webpages), someone has had to find, collect together and sift through a lot of sources to create their text. Teachers constantly have to research their subject and their skills to make sure you are getting the best and most up to date education they can provide. Businesses need to research their products and market on a regular basis to stay ahead of their competitors.

You've probably already guessed that knowledge doesn't magically appear in books or on websites. In those cases (or, at least, for the more reliable books and webpages), someone has had to find, collect together and sift through a lot of sources to create their text. Teachers constantly have to research their subject and their skills to make sure you are getting the best and most up to date education they can provide. Businesses need to research their products and market on a regular basis to stay ahead of their competitors.

Research is going on all around you every day. It's invaluable in the modern world, and therefore a very important skill to master!

break

Creating a research-based project, whether it's coursework, an EPQ, or an extended assignment, should - if done right - increase your enthusiasm for a subject, give you a sense of achievement, and deepen your understanding and knowledge.

The downside, of course, is that it can be very demanding - it may be the largest amount you've ever had to write (so far), and will therefore involve a lot of preparation. If you don't use your time wisely, you could find your motivation and interest quickly declines until deadline panic sets in...

break

But this course is here to help you avoid the possible pitfalls and instead embrace the triumph of a job well done!

But this course is here to help you avoid the possible pitfalls and instead embrace the triumph of a job well done!

We will break down each of the major steps needed to complete that research project:

- setting targets,

- choosing a question,

- finding the right primary and secondary material,

- analysing and interpreting sources, assessing their value, and

- producing a substantial text or project of your own,

so that you can see how to get the work done from start to finish...

Setting Targets

If you've been set a piece of research work at college, then two targets will probably already be available to you:

If you've been set a piece of research work at college, then two targets will probably already be available to you:

1. the project content,

and

2. the project deadline.

BREAK

The first thing you will need to do is to make sure you know exactly what's involved in completing the project and when it is all due in. You should have been given some sort of brief or instructions for your research assignment which, as well as possibly including the subject matter, will tell you what needs to be included in the final project for it to pass. If you don't have that, ask your teacher or mentor for it. Often it will include:

- selecting a topic or area of interest (if the topic or question has not already been provided);

- identifying and drafting the objective(s) for your project (in the form of a question, hypothesis, problem, challenge, etc.) and providing a rationale (explaining the reason) for your choice;

- producing a plan of how you intend to achieve your final project outcome;

- conducting the required research, using appropriate techniques and evaluating source credibility;

- writing up the outcome of your research, evaluating your methods and answering your original question;

- reflecting on your own learning and performance.

REAK

That looks like a scary amount of stuff to do! But it only takes a little bit of breaking down into more manageable targets, in your own words, to suddenly seem a lot more achievable.

Planning and target setting is an important skill and a necessary part of all research projects, so don't skip it or you might be missing out a piece of actual project work! You will probably be asked to review your planning at the end of your project as well, so keeping clear notes from the start and using them throughout your project will help you evaluate your successes and where you could have improved.

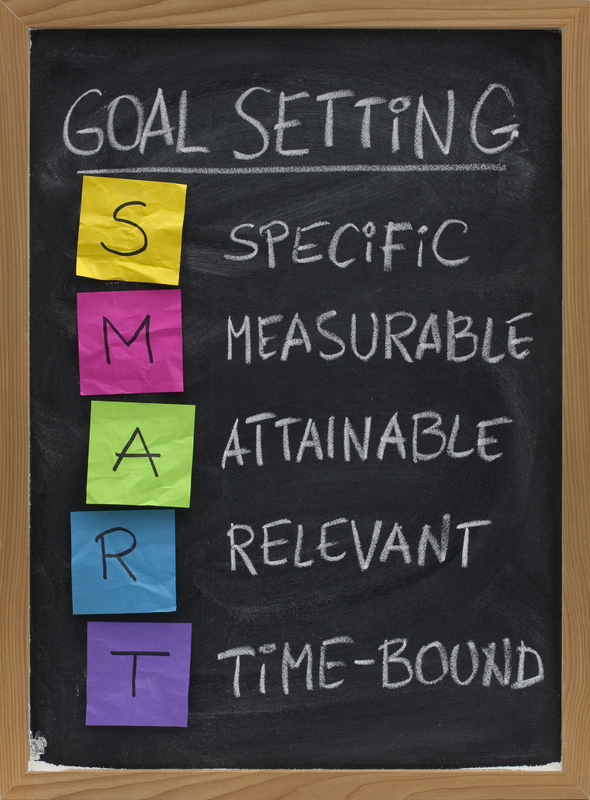

In order to set targets, many people in all walks of life use the SMART target system. SMART stands for:

Specific – outline in a clear statement precisely what is required.

Specific – outline in a clear statement precisely what is required.

BREAK

Measurable – include a measure to enable you to monitor progress and to know when the objective has been achieved.

BREAK

Achievable – objectives can be designed to be challenging, but it is important that failure is not built into objectives. Employees and managers should agree to the objectives to ensure commitment to them.

BREAK

Realistic - focus on outcomes rather than the means of achieving them.

BREAK

Timely - (or time-bound) – agree the date by which the outcome must be achieved.

BREAK

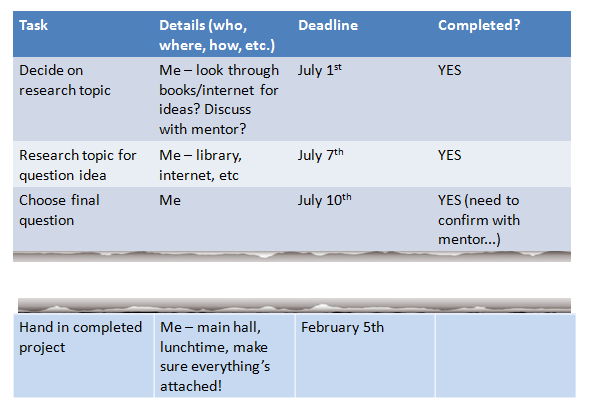

You can easily use this to help you set suitable targets to work through your research project. Break the main brief/instructions down into a number of smaller tasks that are simple to do, achievable and realistic. Then set a realistic timescale for completing each one, and provide yourself with some form of measuring when it has been completed, such as a simple tick box.

One way would be to create a table like this:

Some students have also used Gantt Charts to help them organise their project time. A Gantt Chart lets you visually plan and track projects. It combines a table of tasks to be accomplished along with assignment details and timelines showing their status. Gantt charts were developed by mechanical engineer Henry Gantt more than 100 years ago and have been a staple of project managers ever since. The reason is that they are simple and intuitive to create and use, but display a considerable amount of information at a glance.

You can find some fancy computer software online which will help you create Gantt Charts, but you can also make them fairly simply and for free in Microsoft Excel. If you're not familiar with Excel, this is a good way to start learning to use it. Instead of creating your table in Word, create it in Excel, setting out the task, the date it needs to be completed, and how long you think it should take (duration). Then follow the instructions in this video:

BREAK

To sum up target setting:

To sum up target setting:

before you begin your project, break down the requirements into SMART chunks

and

create a timetable in a format that works for you.

Don't forget to add the final deadline and all your project task deadlines to your homework diary/planner/electronic or paper calendar.

Once you have a plan, you're ready to get started with the research...

BREAK

Quick Activity

Quick Activity

Using your research project brief or instructions, create a target time plan in a format of your choice. You could try out a Gantt chart or use an alternative version, such as a Word table. Make sure your targets are SMART.

This is an essential activity, so you can upload your evidence below if you wish.

You can upload a Word document, an Excel spreadsheet, a pdf print-screen or scanned document, or a png/jpg print-screen of your plan, either in its initial format, or in its final version after you've finished the project, with any ticks, changes and notes included.

Upload your Target Time Plan example here

BREAK

BREAK

Gantt Chart information adapted from http://www.smartdraw.com/gantt-chart/. See also http://www.gantt.com/.

Choosing a Question

Deciding on the question to investigate and narrowing it down sufficiently can take a look of thought. You can easily let this take up too much of the time you have for completing the project, reducing the amount of time you have left to research and write up!

Deciding on the question to investigate and narrowing it down sufficiently can take a look of thought. You can easily let this take up too much of the time you have for completing the project, reducing the amount of time you have left to research and write up!

The best place to start is with your existing knowledge of a topic or subject area and decide on a specific question you want to explore. The question should be relevant to some aspect of the subject, but also be something that interests you.

BREAK

It is very important to be clear about what you are setting out to do, and not to be too ambitious. If you start from an interest in a broad issue, such as social history - example: 'how independent broadcasting has developed' - you need to narrow this down to a more precise enquiry that is manageable within the time and word limits set for the project.

One way of doing this is to take a case-study approach. In the case of the example, you could focus your enquiry mainly on a particular independent broadcasting company, such as London Weekend Television (LWT). Your topic would then be 'The development of London Weekend Television Company'.

But it is a lot more helpful if you actually turn the enquiry into a question rather than a topic heading - example: 'What factors influenced the development of LWT?'. The question focuses your research by forcing you to seek out some 'answers' to it. You now know that you will need to analyse the factors involved and explain and justify your conclusions. Just using the topic heading makes it all too easy to meander around the issues in a rather aimless way and, ultimately, find yourself on the receiving end of the project marker's most common complaints: 'Failed to relate project work to the wider context. Didn't use the information - too descriptive, not enough analysis and explanation.'

BREAK

|

Focusing your research Whatever subject you are interested in - music, art, literature, a particular period/place (e.g. Classical Rome), science, etc. - you must try to define a 'do-able' project for yourself. If you are comparing the work of two composers or novelists, for instance, you cannot hope to look at all their work. And you cannot explore every aspect of an historical period, or of its art or literature. You have to be selective. But how do you know what to select, what to focus on? This is where your knowledge of the broad subject-area comes in. When you are fairly familiar with a subject you know what the important questions and debates are within it. These are what your research enquiry should contribute to in some way. |

BREAK

If you're struggling to come up with a question, try reading around your subject or talking to other people, such as teachers, friends, family, etc. about it. Write down a few potential ideas and turn them into questions to see how you feel about them.

While you are reading around the subject, and the question you will explore is being narrowed down or taking shape, you need to make some preliminary enquiries into what resources are available to you. Check in the ILC, local libraries, online, journals, newspapers, magazines, etc. If you cannot easily get hold of some reliable sources (primary and secondary) then you will have to re-define the enquiry and make changes to your research question.

For the LWT example above, it might be difficult to get hold of the kinds of internal reports, papers and memos that document the company's development and may be held in a private archive. It is certainly likely that you will need to seek permission to view these as soon as possible. You will also need to access government reports and back issues of newspapers that provide context, etc. It would be important to make sure that this kind of information is in some accessible form before you begin.

If you ask, you may find you can use the reference section of any university library, and our ILC sometimes has University of Surrey borrowing cards, so ask a librarian for more information. The ILC or your local library may be able to get books in for you, for example through interlibrary loan schemes.

It is important to remember that you should try and look for primary as well as secondary resources. If primary source material turns out to be too difficult or impossible to access, then you may need to alter your plans.

Making these kinds of enquiries early on, and before you commit to a question or start writing, enables you to change the direction of your work before you have invested too much time in the project.

BREAK

To sum up choosing a question:

- pick a subject you are familiar with and enjoy;

BREAK - turn the topic into a question which will expand your knowledge;

BREAK - if you are struggling to narrow down a question, read around the subject, talk it through with peers, and make a list of possible questions you can then pick from;

and

- check that you can find suitable sources to help you answer the question before you spend too much time on it.

BREAK

Quick Activity

Quick Activity

Have a go at evaluating and improving some project titles in this worksheet. For each title, make a note of what could go wrong and how it could be improved.

This is an essential activity, so you can upload your completed worksheet if you wish.

You can upload your completed worksheet either as a Word document, typed on screen, or as a pdf scan of your handwritten answers.

| Research Skills - Choosing a Question Worksheet | Upload your completed worksheet here |

BREAK

BREAK

Here are a couple more sheets from other people on the best way to choose a good research question:

Writing Studio - What makes a good research question? Includes a checklist to help you decide if your question is good.

Researchable questions and getting to a 'right' answer! Particularly useful if your project is scientific.

BREAK

BREAK

Information on this page was adapted from Chambers, E. & Northedge, A., The Arts Good Study Guide, 1997, The Open University, Chapter 6, Section 8.1, pages 226-228

Finding the Right Primary & Secondary Research

Once you have settled on your research question, it's time to look for sources to help you answer it.

Once you have settled on your research question, it's time to look for sources to help you answer it.

The first important tip here is not to assume the only place to look is the internet. Although the internet will be helpful and will provide some of your evidence, it should be used sparingly, or in equal measure to other types of sources, including:

- books

- academic and scientific journals

- relevant magazines

- newspapers and newspaper archives

- recorded interviews (audio and visual)

- radio and TV programmes

- questionnaires

- statistics

and much more.

BREAK

It is important to consider the types of research you will need to refer to before you begin your search for an answer. For instance, if you are trying to find out the effects of pupil absenteeism on grades, you would need to find official statistics, educational research papers and books, possibly journals and interviews, and maybe carry out your own interviews or questionnaire. But if you were comparing the last works of three major artists, you might need to read scholarly books, journals, diaries, or visit the artists' works first hand for your own primary analysis. If you do need to make additional trips to museums, archives or libraries, make sure to add those to your research targets plan.

BREAK

When analysing research, it is also a good idea to understand what sort of sources and data you are collecting. There are two major types of research you can gather - primary and secondary:

BREAK

Primary research

Primary research is the research you generate by asking questions, conducting experiments or interviews and collating results. This research can take the form of quantitative or qualitative research:

Quantitative research

Quantitative research is inquiry into an identified problem, based on testing a theory, measured with numbers, and analysed using statistical techniques. The goal of quantitative research methods is to determine whether the predictions of a theory hold true. Examples of quantitative research are experiments and closed-question surveys and questionnaires. The best way to remember what this type of research involves is to think of quantitative = quantity, e.g. numbers.

Qualitative research

A study based upon a qualitative process of inquiry has the goal of understanding a social or human problem from multiple perspectives. Qualitative research is conducted in a natural setting and involves a process of building a complex and holistic picture of the phenomenon of interest. Examples of this include case studies, research interviews, observations and field work, as well as open-question surveys and questionnaires. Again, to hep you remember what this type of research involves, think qualitative = quality, e.g. the values that we give to something (good/bad, right/wrong).

The quantitative/qualitative debate

These two forms of research, in spite of the differences stated above, have many things in common. They do, however, offer different perspectives on a subject under study. As a result, some researchers like to use a combination of the two methods to gain both quantifiable and more holistic information. Your research question will ultimately determine which of the two methods you should use.

BREAK

Secondary research

Secondary research is based on the findings from other people's research, and is often the most common type of research students turn to. It involves the gathering of results and information of other people's research from books, reports or the Internet. Selections or summaries are made of the research allowing for evidence to be gathered to support your conclusions.

Secondary research can save time, as you can easily incorporate your sources from Internet searches and books, etc., into your project. However, these need to be referenced, commented upon and analysed. You also need to make sure you avoid plagiarism. Secondary sources may also give you ideas for how to develop, collate and present your own primary research.

BREAK

BREAK

To sum up: it is important to use a mix of sources in your research, including primary sources you have gathered, and secondary sources you can corroborate. If in doubt, use the CRAVEN scale to help you analyse a source and make sure it is reliable and credible.

BREAK

BREAK

Information on this page was adapted from http://teachingcommons.cdl.edu/cdip/facultyresearch/Typesofresearch.html and http://www.hsc.csu.edu.au/design_technology/producing/develop/2662/primary.htm

Source Credibility

The degree of trust we should invest in a source should directly match to its level of credibility. But how do we decide upon this level? In essence, we do so by asking (and responding to) the right sorts of question. These include:

The degree of trust we should invest in a source should directly match to its level of credibility. But how do we decide upon this level? In essence, we do so by asking (and responding to) the right sorts of question. These include:

- Is the source corroborated? Are there other sources which agree with the one in hand?

BREAK - Does it stem from a reputable (reliable) source?

BREAK - Was this source a witness to the reported events or is the evidence purely anecdotal - i.e. reported second-hand (the difference between a primary and secondary account)? If they were there, could their ability to see have been hampered in any way by factors that could cloud or otherwise affect their judgement (loss of memory, inebriation, poor eyesight, shock, age etc.)?

BREAK - Does the source have a vested interest to distort the truth (i.e. do they stand to gain anything by doing so)? Do they have a vested interest to be truthful?

BREAK - Does the source have any relevant expertise (i.e. one that relates to the evidence being presented)?

BREAK - Is the source neutral (i.e. does it present both sides of the argument) or could it be guilty of bias - for example, could the evidence have been interpreted in some way that is less than objective (i.e. one-sided)? Does it employ any emotive language in order to get its points across?

In reality, of course, not all of these questions will need to be addressed. For this reason, you will need to judge for yourself which are the most relevant or appropriate for a particular source, and of course this will vary from context to context.

BREAK

What is important is that you recognise which criteria positively affect, and which negatively affect the credibility of a source and the evidence they present. Corroboration, for example, is a positive credibility criterion. The greater the amount of agreement between sources or evidence, the greater the likelihood that that evidence will be true (although, of course, this will not always be the case).

The same can be said of evidence put forward by reputable sources – i.e. ones with a reputation to uphold. Such sources might include teachers, lawyers, policemen, broadsheet newspapers, news-corporations or more generally, those that can be relied upon to tell the truth.

An ability to see / understand / interpret / judge etc. will also lend weight to evidence. In particular, a primary report – i.e. one given by somebody who was there at the time, can be regarded as more credible than a secondary one, since it offers a first-hand account of the issue on which it is reporting (although this can also be flawed).

Where a source has a vested interest to report the truth (for example, a reputable newspaper or news-broadcaster) or a relevant expertise in the field that is being reported on, we have strong grounds for believing it.

And finally, a neutral account (i.e. one that gives details of both sides of a debate and does so in neutral, i.e. not emotively charged, terms), can be regarded as more credible than one which is slanted or biased (i.e. one-sided or emotively charged).

BREAK

Turning this on its head, where a source is not corroborated, lacks a solid reputation, has no clear ability to see / understand / interpret / judge the issue it reports on; has an apparent vested interest in (i.e. stands to gain from) distorting the truth, lacks relevant expertise and/or offers a one-sided account, then any one of these points will affect its credibility.

You may have noticed that the first letter from each of these credibility criteria spells out the word craven:

BREAK

Corroboration;

Reputation;

Ability to observe/judge;

Vested interest;

Expertise and

Neutrality (or lack of it)

BREAK

This mnemonic is often employed by critical thinkers as a memory aide for dealing with each (although there is no officially ‘correct’ order in which to do this). You should compare your sources using these criteria, and you could use a table format to make a quick comparison, such as in the example below:

BREAK

|

|

Corroboration |

Reputation |

Ability to see/judge etc. |

Vested interest |

Expertise |

Neutrality |

|

Source x |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source y |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source z |

|

|

|

|

|

|

BREAK

Quick Activity

Quick Activity

Have a go at trying out the CRAVEN scale by evaluating a text of your choice using the worksheet below. This is an essential activity, so you can upload your completed worksheet if you wish. You can upload a Word document with typed answers, or a scanned pdf copy of your handwritten answers.

| Research Skills - CRAVEN worksheet | Upload your completed worksheet here |

BREAK

To sum up: when collecting research, it's important to make sure the information is credible (trustworthy and good) - especially if you are using the internet. You need to compare the information given on one website, or in one newspaper article, to the same information in a book or academic journal, and make sure the facts match before using it in your research project. If they don't, you will need to do some more research to see which source has got the right information and stick to using that.

BREAK

Producing a Project #1 - Referencing & Planning

Referencing

Referencing

As you get down to the business of analysing and interpreting the meanings of all your primary and secondary source material (documents, reports, newspaper accounts, books and articles), as discussed in the last two chapters, you will be making notes towards your project report.

If you are not sure about note-taking, take a look at the information and suggestions in the Core Study Skills module on Note-Taking.

In this connection, it is very important to write down full references for all the material you use as you read each item. Then you can easily find particular parts of it again when you need to. And as you do that, you will also be building up your bibliography as you go along.

BREAK

A bibliography is a list of all the sources you refer to in your work which you will attach to the end of your report. It is a good idea to compile this in alphabetical order of authors' surnames. It is much better to build this list gradually, rather than leaving yourself with a lot of fiddly work to do at the end.

BREAK

|

Presenting references in a bibliography When you make a reference to a book you note: author, date of publication, title, place of publication, publisher - and any other relevant information, such as the edition, the volume number, and page references for any quotations you make. It looks like this: Potter, J. (1990) Independent Television in Britain; Volume 4, Companies and Programmes, 1968-1980, London, Macmillan. A reference for a chapter in an edited book is made as follows: Sparks, C (1994) 'Independent production', in S. Hood (ed.) Behind the Scenes: The Structure of British Broadcasting in the 1990s, London, Lawrence and Wishart, pp. 133-54. And you enter an article in a journal in this way: Kandiah, M.D. (1995) 'Television enters British politics: the Conservative Party's Central Office and political broadcasting, 1945-55', Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, vol. 15, no. 2, June, pp 265-84. There are variations in ways of referencing and you may be advised to follow a slightly different layout. But however you do it, you should always provide as much information as you can. A good website for examples of bibliography layouts for all sorts of sources is: http://www.sac.sa.edu.au/Library/Library/Bibliography/bibliography.htm |

BREAK

Whatever style of referencing you use, what matters is that you always make the references in the same way throughout. You should also keep your references together in one place as you work (in a note-book or spreadsheet) so that you don't lose anything. You'll have to keep your source material and notes well organised too, or you will waste a lot of precious time hunting around for things.

BREAK

Planning

Towards the end of this research phase you should be starting to make an outline plan for your project report and even be drafting sections of it as they begin to take shape in your mind.

And, as the deadlines for your active researching stage approaches, you will simply have to call a halt to your investigations. Whatever your topic, there is always more material than you can handle in the time available. You must be ruthless about keeping to your schedule.

BREAK

BREAK

This page was adapted from: Chambers, E. & Northedge, A. The Arts Good Study Guide, (1997) The Open University, Chapter 6, p. 228-9

Producing a Project (Part 2) - Writing Up

Finally, you write up your project report. It is important to recognise that this will go through several drafts. You can't just sit down and write a report on this sort of scale quickly and easily. You should have gathered far too much material for that. And it may take you a little while really to get into the writing.

Finally, you write up your project report. It is important to recognise that this will go through several drafts. You can't just sit down and write a report on this sort of scale quickly and easily. You should have gathered far too much material for that. And it may take you a little while really to get into the writing.

BREAK

Towards the end of the research phase, as you face up to all the writing you'll need to do, you may reach a state where nothing seems to be going on. The interesting planning and discovery stages are behind you and you may start to worry that your research findings aren't good enough. But push on. Once you are fully engaged in writing you will rediscover your enthusiasm. Talking about your work with other students, teachers and friends helps every stage, and especially now when you are really having to sort things out in your mind.

BREAK

Try to achieve different things at each draft stage:

BREAK

First Draft

For the first full draft aim just to get everything down on paper, even if you are dissatisfied with parts of it as you write. Writing a project report can involve a lot more than producing a description of your work. You may have to:

- explain the rationale for what you have done, outlining the background from which your question arose so that your readers can see it's significance;

- explain your choice of research methods; and

- plot a coherent line of argument for your report that takes you towards your conclusions, explaining yourself clearly and justifying your judgements.

So it is quite enough just to get things down somehow at this first stage.

BREAK

Second Draft

As you work towards the second draft you can go back over the parts of the report you're not quite happy with. Concentrate on the structure of your argument, making sure the ideas are adequately linked and sections follow on one from the other towards your conclusions.

BREAK

Third Draft

Now reorganise and reduce your word count until it is closer to the required length (you'll find tips for this in the next subsection).

Remember that you should be using appropriate research material and evidence, either as quotations, statistics or paraphrased information. To avoid plagiarism, use footnotes to clearly acknowledge the work that is not your own.

For a very long project, you may want to use subheadings or chapters to separate different sections of your argument.

Finally, you will need to check that the meaning of each sentence is clear and polish up the report.

BREAK

If you are using a word-processor, these draft stages may be more fluid. But it is still very important not to try to do everything at once, so it is worth behaving as if you were producing several separate drafts, and going through your work with the above different aims in mind.

BREAK

BREAK

This page was adapted from: Chambers, E. & Northedge, A. The Arts Good Study Guide, (1997) The Open University, Chapter 6, p. 229-230

Reducing Word Count

More often than not, you end up needing to reduce your word count in your academic writing, whether it's essays, research projects or coursework assignments. This can be a painful task, because you don’t want to lose the substance of your writing, but you’ve got no choice if you want to hand the piece in with the correct number of words.

However, there are things you can do to reduce word count without affecting the substance of the writing.

Also, make the following quick checks that might let you cut out a lot of word count without making any changes:

- Does the bibliography count?

- Do footnotes count?

- Does the abstract (if there is one) count?

Quite often those can take at least a thousand words off on their own.

BREAK

Reduce word count by simplifying your style

The goal here is to reduce your writing down to its bear bones, leaving little else behind. This may make your writing less pleasant to read, but realistically you can’t be marked down for that. This isn’t a literature contest - it’s about getting your ideas down on paper in the least amount of words possible.

Also remember that the person marking or moderating your work and grading you is most likely going to scan through it at high speed. They may not even notice your prose style particularly, instead looking for the important content to follow the thread of your argument. In that case, you’re actually making the experience more pleasant for them by cutting out the extras in your writing.

BREAK

Delete adverbs

Adverbs (words that describe the way something happens, e.g. gently, always, today...) are usually very deletable in academic writing. At the very least, adverb-verb pairs can be converted into a better chosen verb on its own. For example, “dropped rapidly” could be replaced with “plummeted”.

Tip: using ctrl + f to search through your document for “ly” is a quick way to find a lot of adverbs.

BREAK

Delete adjectives

Whilst adjectives make your writing livelier and more interesting to read, you can nearly always sacrifice them to reduce word count in academic writing. You probably won’t lose credit for duller writing, but you will for exceeding the word count.

Instead of using adjectives, try to keep your prose clear and straightforward, and get straight to the point. Avoid detailed descriptions unless they are absolutely necessary for following your argument and you are sure that the reader needs the detail.

BREAK

Delete connectives

This is another tip that will reduce the flow of the text but is effective in reducing word count. Rather than having longer sentences linked with “and” or “but”, just delete those connectives and have two separate sentences. This will reduce the word count.

Again, remember that your reader will most likely be scanning your text at high speed, not reading it in close detail. Keeping everything clear and simple will make this process easier for them. This could also help you avoid the curse of the super-long-sentence!

BREAK

Delete prepositions

This tactic is a little harder to explain. The idea is to convert chunks of text that use a lot of prepositions (thus adding spaces and increasing your word count) into rephrased, shorter versions without prepositions.

For example, you could replace “tea from China” with “Chinese tea”. It’s only one word, but this adds up if done consistently over a long document.

“Of” is frequently a good candidate for deletion. You can often avoid using “of” just by changing the word order. For example, “writer of fiction” could just as well be “fiction writer”.

BREAK

Delete auxiliary verbs

As with adjectives and adverbs above, auxiliary verbs might make your sentences more aesthetic if read in close detail, but that shouldn’t be your goal with academic writing. As always, keep it concise and to the point.

The auxiliary verbs you might want to remove in academic writing are ones like “could”, “may”, “might” and so on. These can be useful to express tentativeness, which is often a good thing in academic writing, but sometimes it’s just not necessary. Say what you mean directly and drop the extra verbs wherever you can.

BREAK

Replace phrases with words

There are certain phrases in English that have become fixed and are used repeatedly in the same form. You can often replace these with single words to reduce your word count.

Again, there isn’t a set rule for identifying these, but go through your text looking for phrases of several words that seem to be expressing one concept. Whenever you spot one, use a thesaurus to identify one word which conveys the same idea.

BREAK

Eliminate redundancy

'Redundancy' is excessive, unnecessary, or superfluous information, usually involving repeated or added information that is completely unnecessary. You’re likely to have eliminated this in steps above, but there may still be some redundancy in your writing that’s increasing the word count unnecessarily. Definitely delete sequences of descriptive or explanatory words and replace them with one word that summarises the list, even if you lose some of the nuance.

Beyond that, eliminating redundancy is about finding parts of your writing that inadvertently say the same thing twice. You can test sentences by deleting various words and seeing if the meaning actually stays pretty much the same. In those cases, always stick with the deletion.

BREAK

BREAK

Beyond the word and phrase level tricks above, you can also achieve some big reductions in word count by making some structural edits to your work.

BREAK

Reduce the introduction and conclusion

The introduction and conclusion are hugely important parts of a piece of academic writing. Remember, though, that their main function is really to summarise. Give a very concise explanation of your work in the introduction, and reaffirm and back-up your reasoning for it all in the conclusion.

Beyond that, you’re probably wasting word count. There’s no need to go into a lot of detail in these sections - that’s what the main body is for. These sections are all about summarising and condensing. Also remember that you should not include new information in the conclusion - keep it all in the main body.

BREAK

Cut out repetitive chapter-linking sections

Another habit that a lot of people have in academic writing is to ‘tie off’ each section with a mini-summary and then ‘refresh’ the reader again in the beginning of the next one. This is redundant and wastes a lot of word count.

Try to keep section closings extremely concise and short. The reader has just read the content in that section and shouldn’t need anything beyond a short summary of key points to keep things clear.

You can probably delete the ‘refresher’ at the beginning of sections entirely. Just get right into what that section is about. Leave it up to the reader to follow your argument, and make sure that the main content enables them to do so.

BREAK

BREAK

This page is adapted from: https://eastasiastudent.net/study/reduce-word-count/

Footnotes

What are footnotes?

What are footnotes?

Footnotes are notes placed at the bottom of a page. They cite references or comment on a designated part of the text above it. For example, say you want to add an interesting comment to a sentence you have written, but the comment is not directly related to the argument of your paragraph. In this case, you could add the symbol for a footnote. Then, at the bottom of the page you could reprint the symbol and insert your comment. Here is an example:

BREAK

This is an illustration of a footnote.1 The number “1” at the end of the previous sentence corresponds with the note below. See how it fits in the body of the text?

BREAK

_________________________________________

1 At the bottom of the page you can insert your comments about the sentence preceding the footnote.

BREAK

When your reader comes across the footnote in the main text of your paper, he or she can either look down at your comments right away, or continue reading the paragraph and read your comments at the end. Because this makes it convenient for your reader, most citation styles require that you use either footnotes or endnotes in your paper. Some, however, allow you to make parenthetical references (author, date) in the body of your work:

Example of parenthetical reference: Professor Scott asserts that “environmental reform in Alaska in the 1970s accelerated rapidly as a pipeline expansion.”: (Scott 1999,23)

BREAK

Footnotes are not just for interesting comments, however. Sometimes they simply refer to relevant sources - they let your reader know where certain material came from, or where they can look for other sources on the subject. If you're not sure whether you should cite your sources in footnotes or in the body of your paper, you should ask your subject teacher or EPQ mentor.

BREAK

Where does the little footnote mark go?

Whenever possible, put the footnote at the end of a sentence, immediately following the period or whatever punctuation mark completes that sentence. Skip two spaces after the footnote before you begin the next sentence. If you must include the footnote in the middle of a sentence for the sake of clarity, or because the sentence has more than one footnote (try to avoid this!), aim to put it at the end of the most relevant phrase, after a comma or other punctuation mark. Otherwise, put it right at the end of the most relevant word. If the footnote is not at the end of a sentence, skip only one space after it.

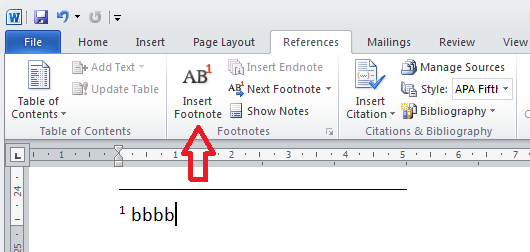

Creating a footnote in Word (or other word-processing programs, such as Pages) is usually very easy. Place your mouse cursor where you want the footnote to go, and find the footnote creation button on the toolbar. In Word it can be found under the 'References' tab:

BREAK

What's the difference between footnotes and endnotes?

The only real difference is placement - footnotes appear at the bottom of the relevant page, while endnotes all appear at the end of your document. If you want your reader to read or refer to your notes right away, footnotes are more likely to get your reader's attention. Endnotes, on the other hand, are less intrusive and will not interrupt the flow of your paper. Again, check with your subject teacher or EPQ mentor if you're not sure which to use. Endnotes can also be added using the toolbar button in Word.

BREAK

If I cite sources in the footnotes (or endnotes), how is that different from a bibliography?

Sometimes you may just be asked to include these as well - especially if you have used a parenthetical style of citation. If you are using someone else's words, statistics, illustrations, etc. you must make it clear that these are not your own work to avoid being accused of plagiarism. Taking someone else's work and using it as your own can result in a failed piece of coursework or research project.

A "works cited" page is a list of all the works from which you have borrowed material. Your reader may find this more convenient than footnotes or endnotes because he or she will not have to wade through all of the comments and other information in order to see the sources from which you drew your material. A "works consulted" page is a complement to a "works cited" page, listing all of the works you used, whether they were useful or not.

BREAK

Isn't a "works consulted" page the same as a "bibliography" then?

Well, yes. The title is different because "works consulted" pages are meant to complement "works cited" pages, and bibliographies may list other relevant sources in addition to those mentioned in footnotes or endnotes. Choosing to title your bibliography "Works Consulted" or "Selected Bibliography" may help specify the relevance of the sources listed. It is highly unlikely you will need to use both.

BREAK

If in doubt, stick to using footnotes and a bibliography, as these are the most commonly used methods of citation and research referencing. Ask your teachers about what form of citation they want you to use.

BREAK

BREAK

This page is adapted from: http://www.plagiarism.org/citing-sources/what-are-footnotes/

Producing a Project #3 - Finishing Off

Once you've finished writing up your project and you're on your final version, ready for handing in, you need to make sure you have gathered everything together, in the correct order, ready for deadline day. This stage should be at least a week before the deadline, just in case there are any last minute elements you need to add or changes to be made.

Once you've finished writing up your project and you're on your final version, ready for handing in, you need to make sure you have gathered everything together, in the correct order, ready for deadline day. This stage should be at least a week before the deadline, just in case there are any last minute elements you need to add or changes to be made.

BREAK

Make a checklist of project items, either using the original research project brief, or using one provided by your teacher/mentor, and tick each item off as you complete it. Ask in advance if there is anything on that checklist you're not sure about, and if you are compiling your own list, double check in advance with your teacher/mentor that you have covered everything. You can also ask to see exemplar o past student work to get an idea of what a final research project should look like.

You may be asked to include any of the following elements to complete your research project:

- A front cover, including your student details and project details.

BREAK - A thesis or hypothesis.

BREAK - An abstract - this is a bit like the section on the back or inside cover of a text book, giving you an idea of what to expect from the book, and might need to include:

- what the project is about,

- what sort of research you used and how you gathered it, and

- what your final conclusion is.

An abstract is usually about 250 words at most, but check the word count you have been given, especially if it is part of your overall word count.

BREAK - The main part of the research project, including your introduction, arguments (middle) and conclusion.

BREAK - An evaluation of how well you felt your project and your overall research went.

BREAK - A bibliography.

BREAK - A source review/evaluation.

BREAK - Other paperwork, possibly including your original project plans, research lists, timescales, project journals, presentation slides, signed confirmation that the project was all your work, etc.

BREAK

Make sure you gather everything together, in the correct order and in the format required. Then all you have to do is keep it somewhere safe until you can hand it in!

Job done.

Summary and Review Quiz

A research project can teach you some extremely valuable skills, including:

A research project can teach you some extremely valuable skills, including:

- how and where to find source material information;

- how to make your own investigations;

- strategic planning;

- time management;

- analysing and interpreting primary and secondary source material;

- forming your own conclusions;

- writing clearly and concisely when you have a lot of very varied material to present; and

- making a convincing case.

Despite the time it may take up, a research project can be one of the most rewarding pieces of work you will complete during your time at college.

BREAK

To sum up, when you undertake your own research project:

- Don't be too ambitious at the outset; define a narrowly focused question which you can investigate fully in the time available.

BREAK - Make a timetable for your work and stick to all deadlines; start early and allow plenty of time for each project stage (especially writing the report).

BREAK - Make sure you include analysis and evaluation in the project, not just explanation.

BREAK - Try to achieve different things in each of your draft stages.

BREAK - Use the CRAVEN scale to help you decide if a source is credible.

BREAK - If you are really struggling with any stage of your project, make sure you talk to your teacher or mentor as soon as possible about your concerns, and ask to see exemplar work.

BREAK

Research Skills Review Quiz

Research Skills Review Quiz

Now that you have worked through the Research Skills course, you need to complete the Review Quiz. Open the Quiz in Word and either print it out and handwrite, or type in your answers on the screen.

You must upload either a scanned pdf or a saved Word version below.

| Research Skills Review Quiz |

BREAK

BREAK

Congratulations on completing this course - hopefully you will soon be celebrating the successful completion your research project as well!