Fallacies / Flawed Reasoning

The term ‘fallacy’ is often used in a loose way to mean any falsehood, for example in: ‘It is a fallacy that garlic is a health-food.’

XXX

Logical fallacies are common errors of reasoning. If an argument commits a logical fallacy, then the reasons that it offers don’t prove the argument’s conclusion. (Of course, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the conclusion is false, just that these particular reasons don’t show that it’s true.) For example: ‘it is a fallacy to claim that garlic is a health food on the strength of low heart-attack incidence in some countries where garlic is eaten.’

XXX

In some cases fallacious reasoning is unintentional on the author’s part. But on occasions it may be a deliberate ploy to ‘win’ a debate, or persuade the audience.

XXX

There are literally dozens of logical fallacies (and dozens of fallacy web-sites out there that explain them). Many have names (some going back centuries), and are often referred to as the Classic Fallacies. In this short course, we will only look at twelve of the most commonly used ones, but take a look at the links to other sites on the subject for the wider variety.

XXX

|

|

Ad Hominem

Unfairly attacking the person making the argument, rather than the issue. Can also mean attacking the character and/or reputation of those that agree with the argument.

The Latin means 'at the man/person'.

|

|

|

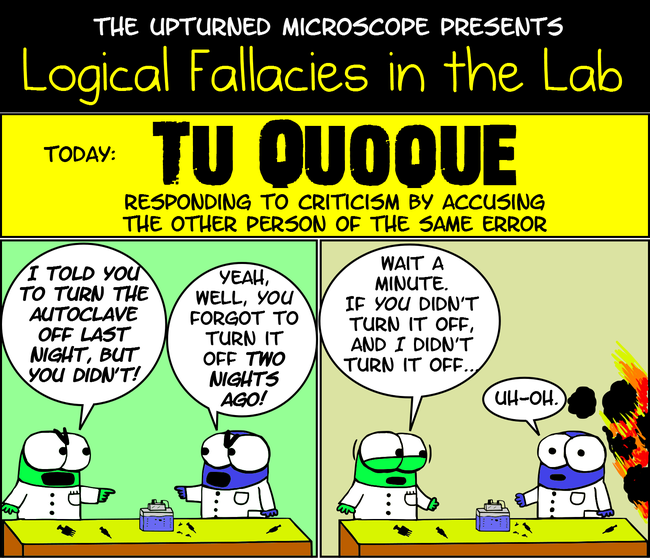

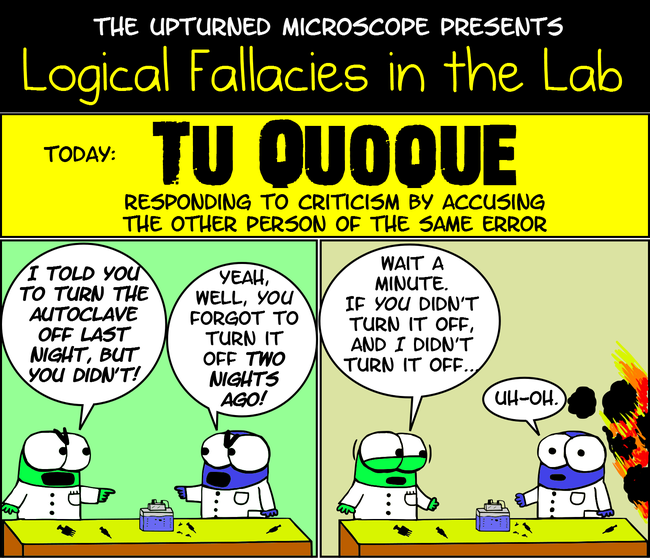

Tu Quoque

Latin for 'you too', this means justifying one wrong with another. This fallacy involves using other people's faults as an excuse for your own, reasoning that because someone or everyone else does something wrong, it is okay for us to do it.

|

|

Please don't do this!! It's just a fallacy!

|

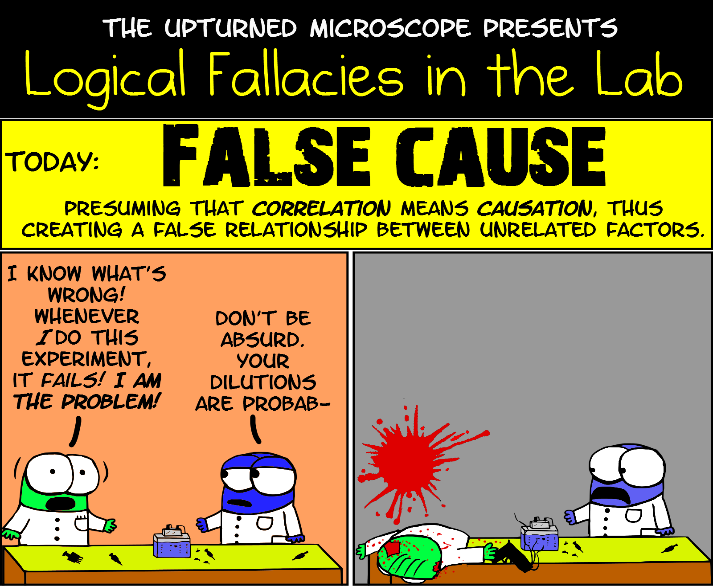

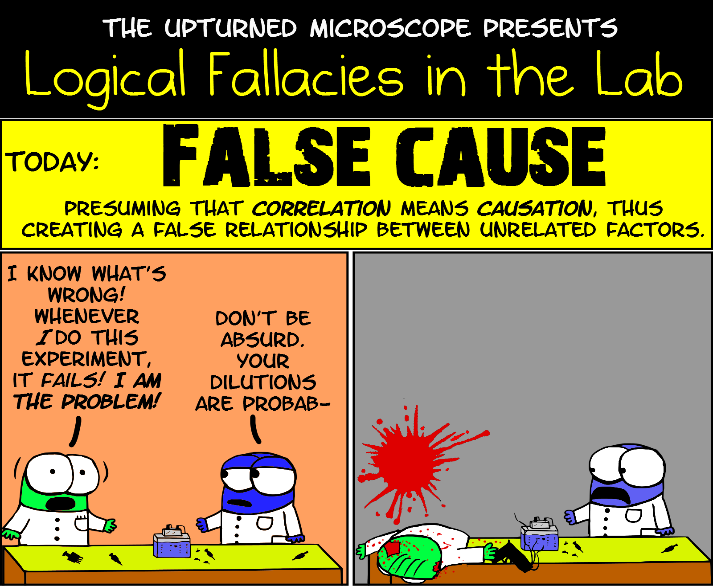

Cause Correlation and Post Hoc (also known as False Cause)

This is when two events are wrongly (or without evidence) linked to each other as cause and effect of the same thing - just because the two events or things are found together does not necessarily mean that they are correlated or linked. Post Hoc particularly refers to a connection made because one event appears to have directly followed another.

|

|

|

False Dichotomy / False Dilemma

Sometimes known as the 'Marmite' fallacy ('love it or hate it?'), this type of fallacy argues that there are only two possible outcomes, when in reality there may be many other outcomes not being taken into consideration.

|

|

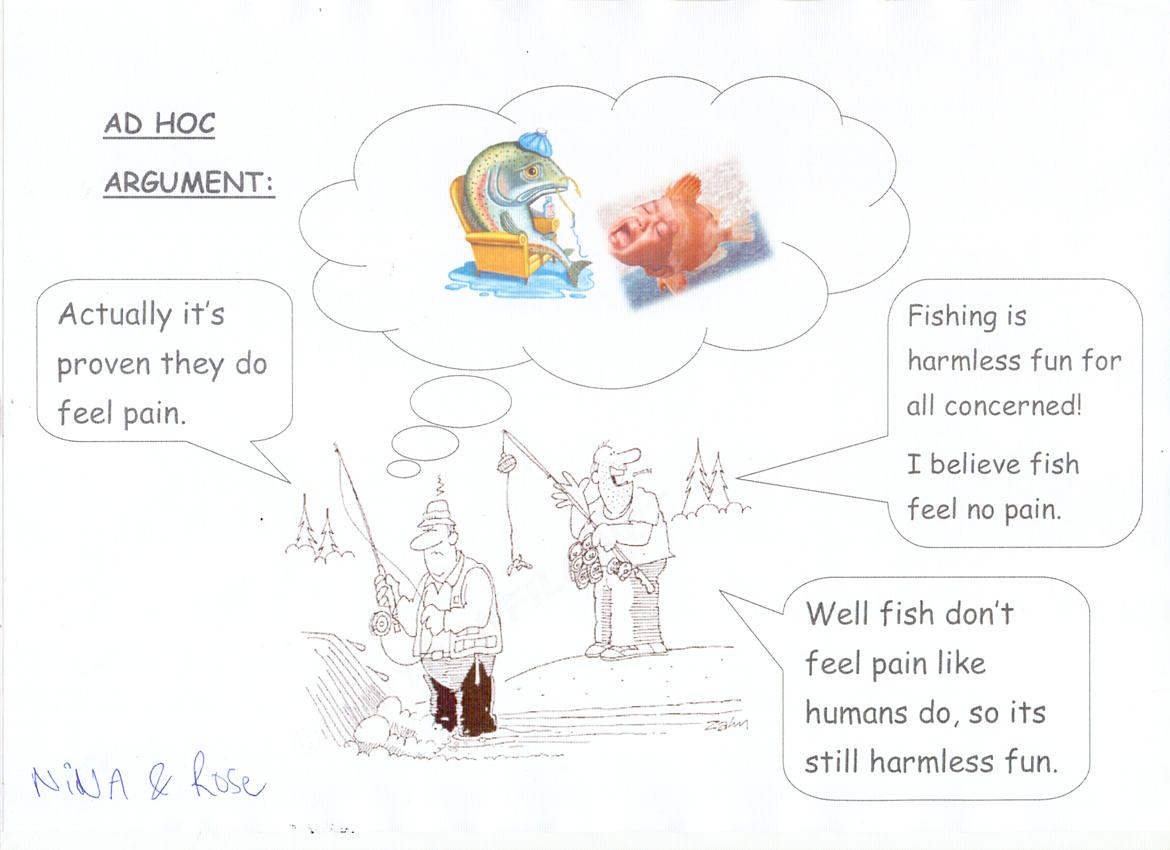

Ad Hoc

Also known as the 'Questionable Cause' or 'Questionable Explanation', it is sometimes argued that this isn't a fallacy at all. When a claim has been made, and a legitimate objection has been raised to this claim, there may be no other option but to revise the original claim.

For example, some people might argue that fishing is harmless fun for all concerned, based on the premise the fish feel no pain. But if convincing evidence was found to prove that fish do in fact feel pain, an ad hoc argument might be that fish don;t feel pain the same way that humans do in order to still argue that fishing is harmless fun.

|

|

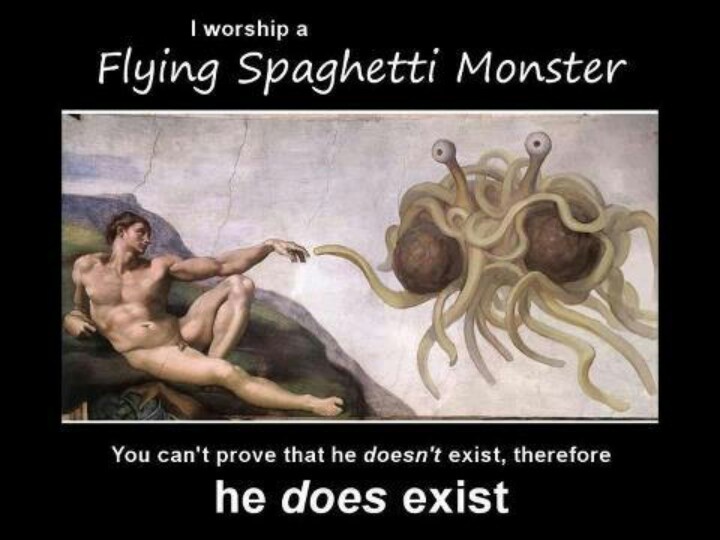

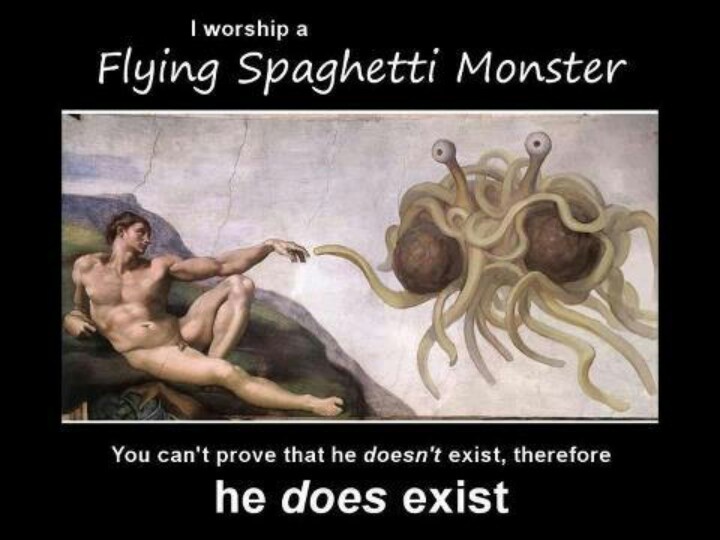

Argument from Ignorance

This is an argument that takes lack of evidence as grounds for denying something, or lack of contrary evidence as grounds for asserting something. Sometimes, it is not the claim that is fallacious but the reasoning.

The classic example of this is "God exists because you can't prove He doesn't!", or conversely, "God doeesn't exist because you can't prove he does!". If you cannot prove something (and neither can the person you are aiming the argument at), then your very conclusion has to be flawed as well.

|

|

|

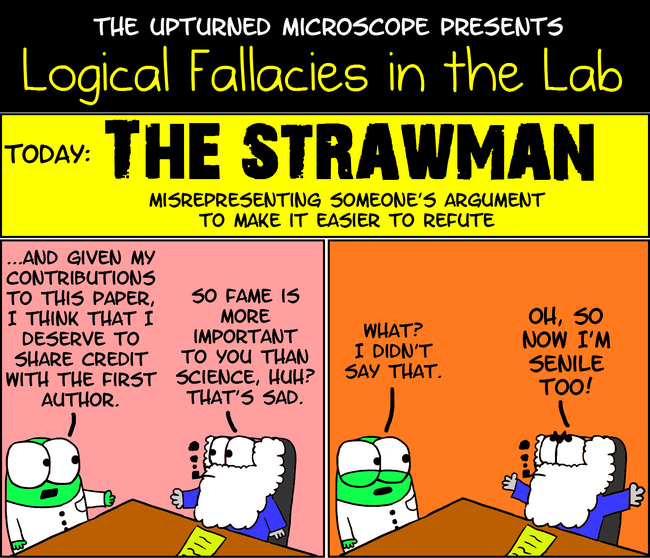

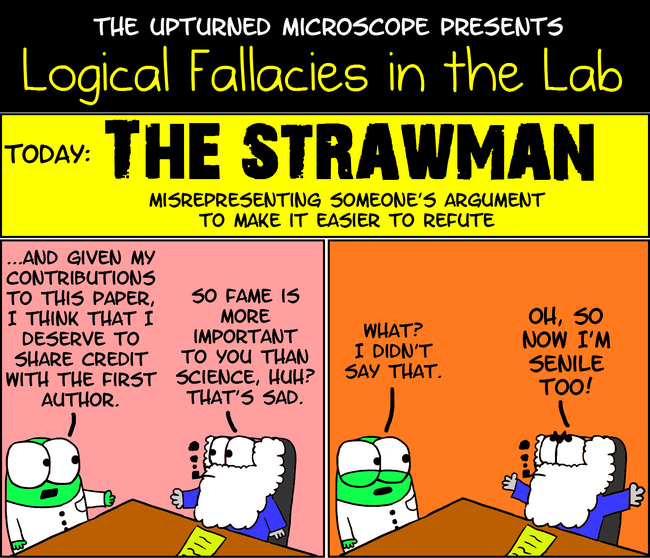

Straw Man

Misrepresenting or distoring an opposing viewpoint or argument in such a way that it is easily put down.

|

|

|

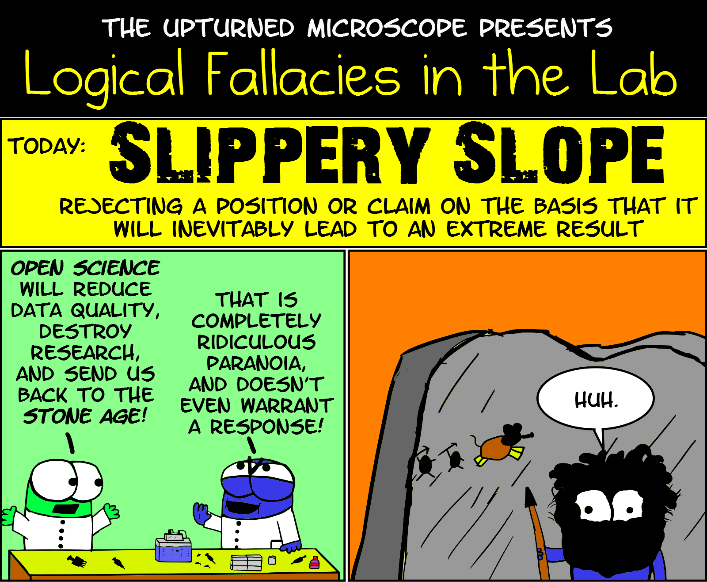

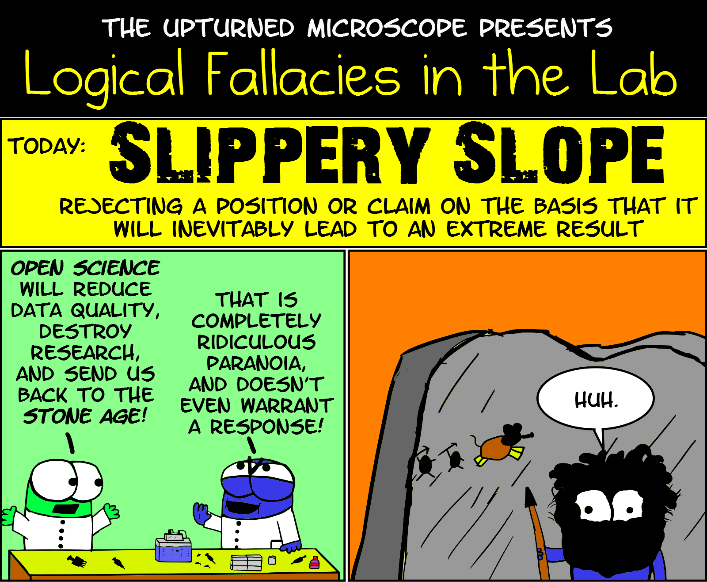

Slippery Slope

Sometimes one event can set of a chain of consequences; one thing leads to another, as the saying goes. The slippery slope fallacy is committed by arguments that reason that because the last link in the chain is undesirable, the first link is equally undesirable.

NB. This type of argument is not always fallacious. If the first event will necessarily lead to the undesirable chain of consequences, then there is nothing wrong with inferring that we ought to steer clear of it. We need to judge the adequacy of the inital claim to be sure...

|

|

|

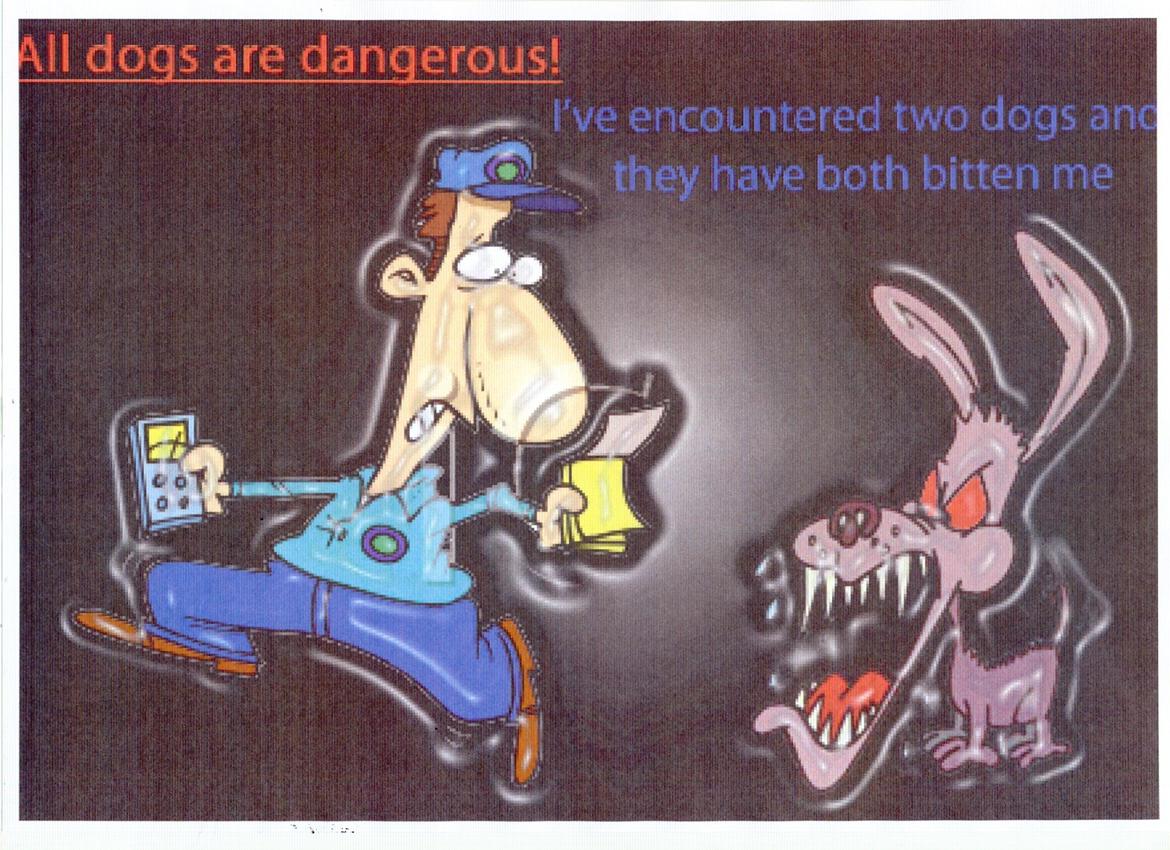

Overgeneralisation / Anecdotal Evidence

This argument uses a small number of instances to create a general conclusion. This is clearly a fallacy because the conclusion is based on an insufficient amount of evidence.

For example: ‘Manchester is a crime-ridden city. Both times I’ve been there I’ve been mugged.’

|

|

Click the above image to see it in full size.

|

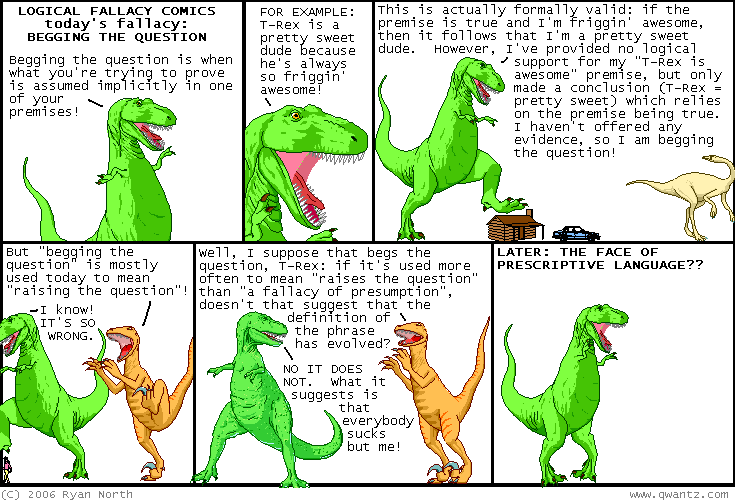

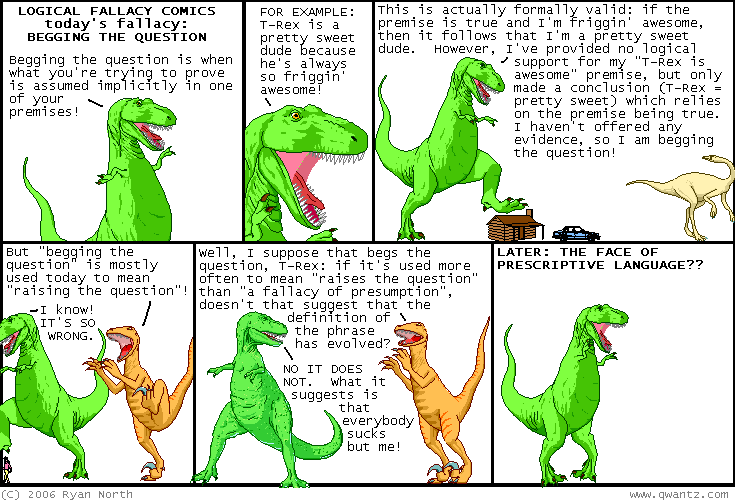

Begging the Question

Circular arguments are arguments that assume (in the premises) what they’re trying to prove. If the conclusion of an argument is also one of its reasons, then the argument is circular.

The problem with arguments of this kind is that they don’t get you anywhere. If you already believe the reasons offered to persuade you that the conclusion is true, then you already believe that the conclusion is true, so there’s no need to try to convince you.

If, on the other hand, you don’t already believe that the conclusion is true, then you won’t believe the reasons given in support of it, so won’t be convinced by the argument.

In either case, you’re left believing exactly what you believed before. The argument has accomplished nothing.

|

|

Confusing Necessary and Sufficient Conditions

Just because something is necessary for some outcome does not mean it is also sufficient.

Necessary conditions are conditions which must be fulfilled in order for an event to come about. It is impossible for an event to occur unless the necessary conditions for it are fulfilled. For example, a necessary condition of you passing your A-level Critical Thinking is that you enrol on the course. Without doing so, there’s no way that you can get the qualification.

Sufficient conditions are conditions which, if fulfilled, guarantee that an event will come to pass. It is impossible for an event not to occur if the sufficient conditions for it are fulfilled. For example, a sufficient condition of you passing AS Critical Thinking is that you get enough marks on the two exams. If you do that, there’s no way that you can fail.

Some arguments confuse necessary and sufficient conditions. Such arguments fail to prove their conclusions.

Example: ‘The engine won’t run unless fuel is getting through. So all you have to do to start it is clean the fuel line.’

|

|

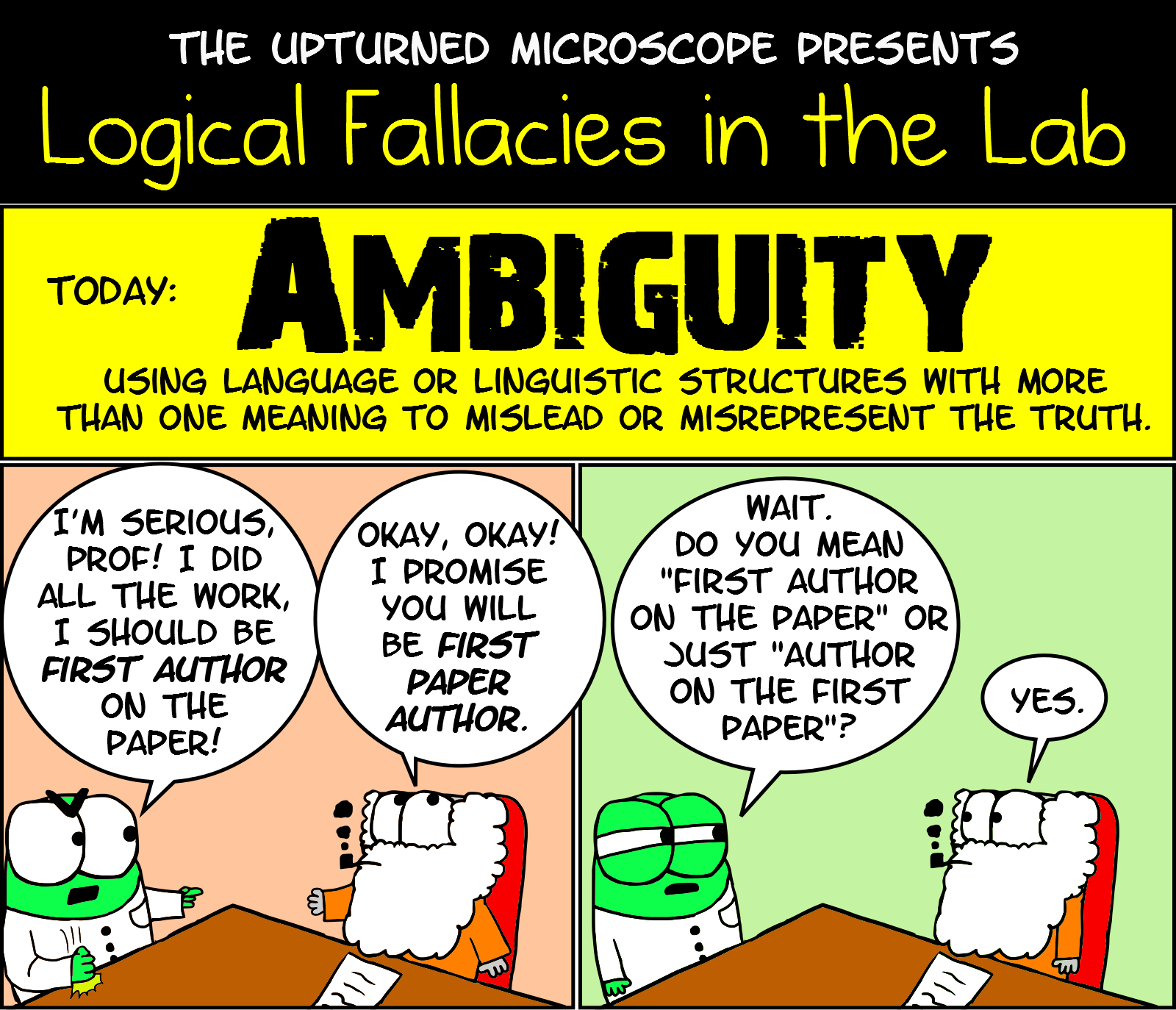

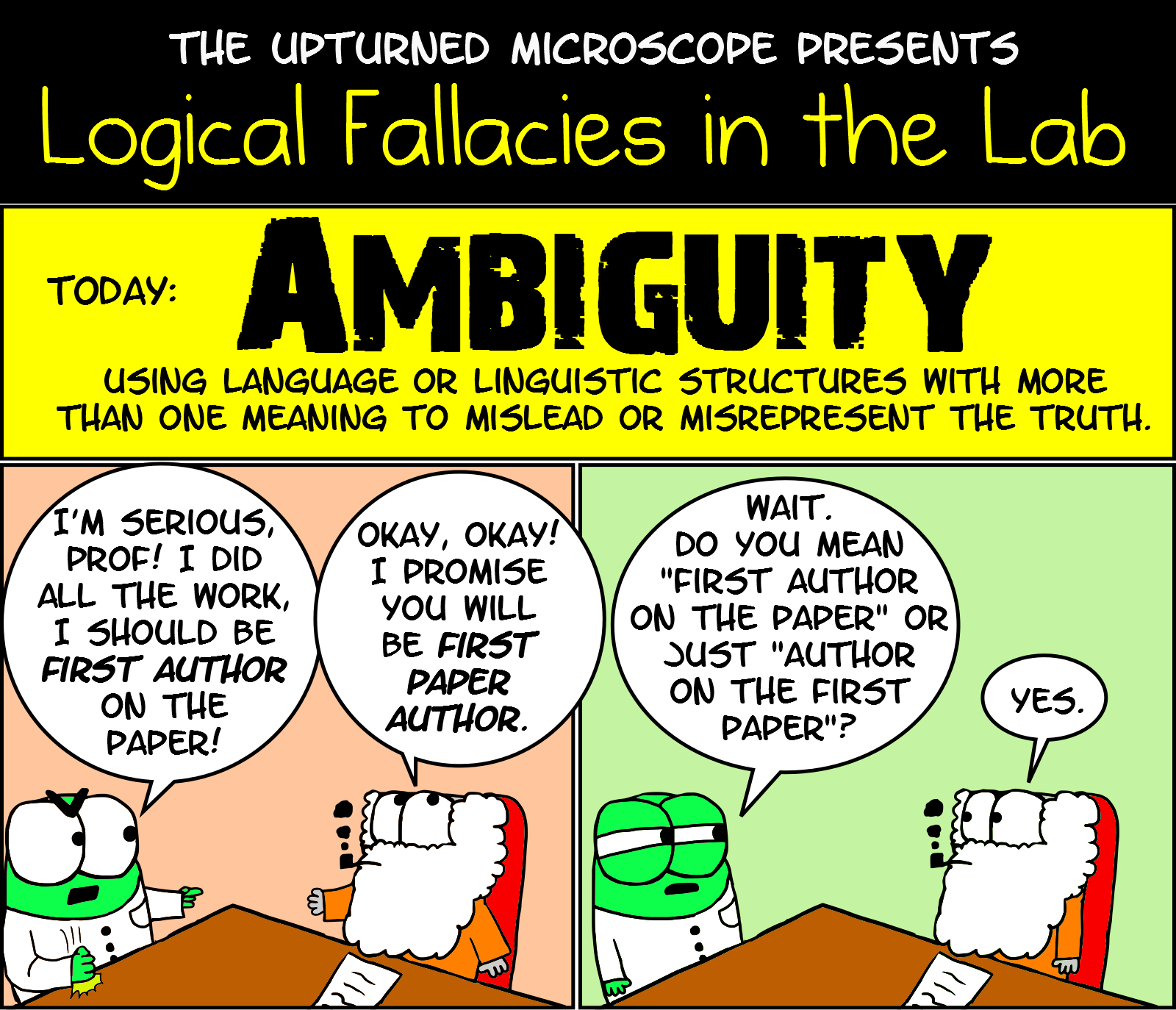

Confusion / Equivocation

Sometimes an expression is misused, or used in a purposely confusing or ambiguous way. This is also known as equivocation (or ambiguity), especially when the same word is used with different meaning in the same argument. It may result from ignorance or it may be a deliberate ploy to mislead.

Example: ‘The average family has 2.4 children and the Burton family is about as average as you can get. Therefore the Burtons must have either two or three children.’

|

XXX

You need to be able to recognise each of these fallacies, and also to explain what is wrong with arguments that commit them. Once you’ve learned what the fallacies are, pay attention and see if you can spot any of them being committed on TV, the radio, or in the press. They're particularly popular in politics...

Click here for the full poster version of this image, or visit: https://yourlogicalfallacyis.com/

Click here for the full poster version of this image, or visit: https://yourlogicalfallacyis.com/

Click here for the full poster version of this image, or visit: https://yourlogicalfallacyis.com/

Click here for the full poster version of this image, or visit: https://yourlogicalfallacyis.com/