Critical Thinking

Additional Evidence, Counter-Examples & Analogies

Analogies

Analogies can be used as an effective shortcut for getting to grips with a difficult idea.

Analogies can be used as an effective shortcut for getting to grips with a difficult idea.

For example, in the introduction to the AQA Critical Thinking course book, an ‘argument’ was compared to the human body:

- The human body is not just a single unit, but rather, a complex one which can be broken down into many separate parts. Each of these parts has a function: the heart pumps blood around the body; the eyes provide us with sight and the ears, sound etc. and these individual functions combine to contribute to the body’s functioning as a whole. An argument is like this, composed of separate parts, each with a specific role.

Here, a comparison is drawn between an idea that might be new to you and fairly complex (that of ‘argument’) and one that you should all be familiar with (the body). Because there are suitable similarities between the two things being compared this was a legitimate way of communicating a difficult idea. Here are some more examples for you to think about:

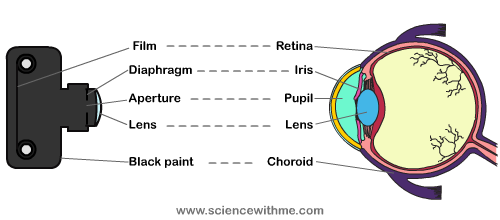

- The eye is like a camera.

- Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that. (Martin Luther King).

- Religion is the opium of the masses (Karl Marx).

- ‘When they debate as to what the sound of the SLR engine was akin to, the British engineers from McLaren said it sounded like a Spitfire. But the German engineers from Mercedes said "Nein! Nein! Sounds like a Messerschmitt!" They were both wrong. It sounds like the God of Thunder, gargling with nails. (Jeremy Clarkson, when driving the McLaren Mercedes SLR through a tunnel.)

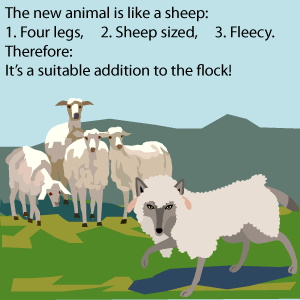

Analogies are often appealed to in arguments because, if we accept that something holds true in one case, then it should also hold true in parallel cases (i.e. those which are suitably similar).

Perhaps the most famous example of this type of reasoning was put forward by William Paley who argued for the existence of an ‘intelligent designer’ (God) by drawing an analogy with a watchmaker:

- In crossing a heath, suppose I pitched my foot against a stone and were asked how the stone came to be there, I might possibly answer that for anything I knew to the contrary it had lain there forever; nor would it, perhaps, be very easy to show the absurdity of this answer. But suppose I had found a watch upon the ground, and it should be inquired how the watch happened to be in that place. I should hardly think of the answer which I had before given, that for anything I knew the watch might have always been there. Yet why should not this answer serve for the watch as well as for the stone? Why is it not as admissible in the second case as in the first? For this reason, and for no other, namely, that when we come to inspect the watch, we perceive—what we could not discover in the stone—that its several parts are framed and put together for a purpose … [The requisite] mechanism being observed … the inference we think is inevitable, that the watch must have had a maker. Every observation which was made in our first chapter concerning the watch may be repeated with strict propriety concerning the eye, concerning animals, concerning plants, concerning, indeed, all the organized parts of the works of nature. … [T]he eye … would be alone sufficient to support the conclusion which we draw from it, as to the necessity of an intelligent Creator. …

(William Paley, ‘Natural Theology’ – adapted from Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

We could simplify Paley’s argument as follows:

- A watch displays order (all the parts fit together) and purpose (it has a specific function) and for this to be so, it must have been designed (by a watchmaker).

- Analogically, when we look at objects in the world (the eye, animals, plants etc.) we realise that these too display an order and purpose that is too complex to have come about by chance (as with the stone). They must thus be the product of an intelligent designer (God).

So an analogy is drawn between objects which have been designed for a purpose and the universe. The inference (that the universe too must have a designer) rests upon the assumption that the two cases are suitably alike for the points that hold true of the first to hold true of the second. If we accept this, the analogy works; if we don’t, it doesn’t.

So an analogy is drawn between objects which have been designed for a purpose and the universe. The inference (that the universe too must have a designer) rests upon the assumption that the two cases are suitably alike for the points that hold true of the first to hold true of the second. If we accept this, the analogy works; if we don’t, it doesn’t.

But what grounds might there be for reaching such a judgement? In deciding whether or not an analogy is effective, three things need to be taken into account.

First, you will need to be clear about which two things are being compared (in the above example, a mechanism which has been designed, and the universe).

Secondly, you will need to consider their similarities and differences (whether or not the universe displays a similar sort of design to the watch; whether something manufactured is suitably similar to something natural etc.).

Thirdly, you will need to judge whether the similarities are significant enough, and that the two cases do not differ in any important aspects, for the analogy to be effective (if the level of design displayed by the watch is significantly different to that displayed by the universe, then the analogy should be rejected).

This last point is significant because if, as is often the case, there are noteworthy differences, the example will be guilty of committing the weak analogy fallacy:

- Using a condom to prevent the spread of AIDS, is like trying to put out a fire with paraffin (Cardinal Alfonso Lopez Trujillo [paraphrased slightly])

These words were uttered by one of the leaders of the Roman Catholic Church (Panorama, ‘Can Condoms Kill?’). They were preached alongside information contained in a 20 page document which urged that condoms, far from preventing the flow of aids, actually contributed to it. Trujillo argued condoms had tiny microscopic holes in them which allowed the transmission of the HIV virus (this has since been scientifically refuted) and this message was taken to Africa, a Continent ravaged by AIDS. It should be clear that, although visually powerful, the analogy is a weak one. It attempts to convey the message that condoms are responsible for the spreading of AIDS (it was argued that, not only do condoms not work, but they also encourage an irresponsible attitude towards sex) in much the same way that paraffin contributes to the spreading of fire! But the differences between the two cases are so substantial, the analogy fails – although its emotional force blinded many people to this. We might summarise these differences as follows:

- Condoms are used to prevent AIDS whereas paraffin is used to encourage fire.

- The failure rate of condoms is roughly 1.5%; the failure rate of paraffin (to put out a fire) would be 100%.

- Condom use can be regarded as a responsible activity; putting fire out with paraffin, an irresponsible one!

And no doubt there are many others. In fact, it would be difficult to find any significant similarities between the two cases that could help the analogy. Contrast this example with the following one:

- Using a condom to prevent the spread of aids is like wearing a raincoat to prevent oneself getting wet in a thunderstorm.

Now of course there is at least one important difference here – the threat of contracting AIDS is significantly more dangerous than the threat of getting wet. However, because there are a suitable amount of relevant similarities, i.e.:

- Both offer an effective method for preventing something happening.

- Both offer protection in the form of a barrier from an external threat.

the analogy can be regarded as a fairly strong one. Coming to a decision about whether the relevant similarities between the two things being compared outweigh the differences is the key to evaluating an analogy. The notion of relevance is important here because, whilst it would be fairly safe to argue that:

- your car is a similar make and model to mine and has the same engine, so they probably travel at similar speeds.

because make, model and engine size are all relevant factors for determining a cars speed, it would be exceedingly unsafe to argue that:

- Your car is a similar colour to mine, so they probably travel at similar speeds!

Obviously, the colour of a car has no effect on the speed at which it travels.

XXX

XXX