Writing Essays and Assignments

| Site: | Godalming Online |

| Course: | Study Skills |

| Book: | Writing Essays and Assignments |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Monday, 23 December 2024, 1:23 AM |

Description

Mmm

Introduction

Essays and assignments are a dialogue between you and the reader (in the case of college, usually, your teacher or the examiner/moderator).

They allow you to demonstrate what you know about a topic and to receive feedback to improve your learning and skills.

They're a good practice of exam technique.

They give you a chance to revise a topic, analysing and evaluating it more thoroughly.

And they help you to develop your own independent learning skills through creating something original, researching, structuring a logical argument, expressing your point succinctly, and evaluating to your own conclusion.

They should, therefore, be seen as a really useful and important part of your courses - something to enjoy exploring and developing.

BREAK

Unfortunately most students simply see them as a time-consuming burden, especially when the effort put in doesn't seem to match the grades and feedback. And sometimes it just feels impossible to even know where to start...

BREAK

In this course book, we will look at how to make essay or assignment writing a simple, planned process that will allow you to explore the topic, structure your answer, conclude the question, and achieve the excellent marks you're fully capable of.

BREAK

Each subject you're studying will have a slightly different approach to essay or assignment writing, which your teachers will explain to you, but there are some general rules and tips that always hold true. These are:

Each subject you're studying will have a slightly different approach to essay or assignment writing, which your teachers will explain to you, but there are some general rules and tips that always hold true. These are:

- planning (do not skip this!),

- structure,

- answering the question correctly (and therefore coming to an appropriate conclusion),

- layout and language,

- reviewing and proof reading, and

- acknowledging feedback.

So let's begin before the beginning and write that perfect essay...

Planning - Why?

Why plan?

Why plan?

Remember when you used to get some pretty good grades for essays at school? Yet somehow, when you started at college, your feedback started including such unexpected comments as:

"You're not structuring right!"

"It doesn't make any sense!"

"You're waffling/not answering the question properly."

"Your points are all over the place!"

"You need to back up your points with more evidence."

"You're not including enough evaluation." Etc.

How did you go from being good at something to feeling rubbish about it in a matter of months?

Simple. GCSE essays were a lot easier, shorter, and didn't required much, if any, planning - A level essays do.

BREAK

Planning is generally avoided by students because:

- "it takes too long!" (No, it doesn't.)

- "I can do it just as easily in my head." (No, you can't.)

- "I prefer to just start writing and let it flow/see what happens..." (Not a great idea anymore...)

- "I don't usually use the plan." (Well, you probably should!)

- "It doesn't help." (Then you're doing it wrong.)

BREAK

Planning should be done because:

- it helps you to structure your argument.

- it helps you to correctly answer the question.

- it helps you to meet word limits.

- it helps to focus your points.

- it reminds you of exactly what you need to do to get the top grades.

How? Keep reading...

Planning - How?

As with any new skill, the first few times you try out planning, you might find it clunky or a bit time consuming, but the more you practice planning, the quicker and easier it will become, especially for use in exams!

As with any new skill, the first few times you try out planning, you might find it clunky or a bit time consuming, but the more you practice planning, the quicker and easier it will become, especially for use in exams!

BREAK

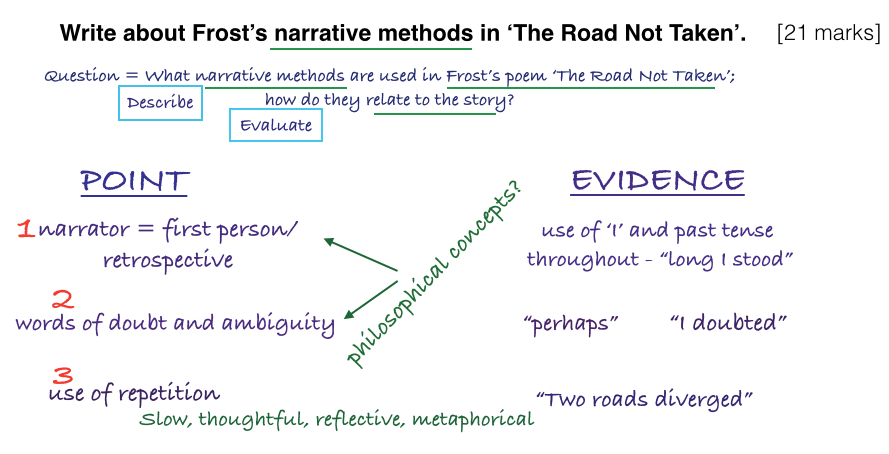

Here's our quick guide to quick planning:

For the even quicker quick guide to quick planning, just read the BOLD words...

You will need plain or lined paper/Word or PowerPoint open; coloured pens/pencils, etc.; relevant text books; and the essay/assignment title!

BREAK

- An academic essay should start with a question - that, after all, is what you'll need to answer in your conclusion. If the essay or assignment title you've been given doesn't appear to be a question, then turn it into one.

For example: "Discuss the idea that Hamlet was mad." becomes "Was Hamlet mad?"

Once you have your question, the first part of your plan should be your tentative answer - do you agree or not?

Use the BUG technique to make sure you're definitely asking and answering the right question.

BREAK - Now you have your question and rough idea of an answer, it's time to prove it. Most essays require between 3-5 points, depending on their word count (although you should check with your teachers about the precise number for each subject). A 1,500 word essay might have 3 main points, for example. So your next step is to list three reasons for your answer.

For example, Hamlet wasn't mad because: (1) other people could also see the ghost of his dead father, (2) he is able to rationalise his thoughts, (3) he specifically states he is only pretending.

BREAK - Once you have your points, you need to spend a bit of time finding the evidence for these - this is probably the longest part of planning, but don't be fooled into thinking this is slowing you down - you'd have to do this anyway! Use your text books and class notes to gather the facts. Make quick notes of evidence/examples next to or underneath each answer.

BREAK - If it's relevant to your question, while you're finding evidence to back up your answer, you should also be looking for examples that might argue against your answer - counter-arguments are all part of analysing and evaluating your argument. Your essay title might even expect this of you (argue for and against). Note these too.

BREAK - Now take a look at your planning notes so far and note (with a number or other key) which argument (and/or counter-argument) you will write up first, then second, then third.

That may look like a lot of work, but in practice it can actually look as simple as this:

BREAK

Quick Activity

Quick Activity

Have a go at creating a basic plan for an essay or assignment you are working on. Try out the BUG technique on the question, and come up with at least three examples with notes on where to find evidence/counter-examples. You can write your plan in any kind of layout that works for you - consider bullet-point lists, mind-maps, etc. This is an essential activity, so you can upload your evidence if you wish. Your upload can be a word document or a scanned pdf of a handwritten example.

Upload your completed basic Essay Plan here

BREAK

So now that you have your rough plan ready, you're ready to use it to start writing.

______________________________________________________________________

Extra! Extra! Essay Writing Frames

For a more in-depth planning process, consider working with an essay writing frame - one example can be found by clicking here.

You can amend this to suit the types of elements you need to include for subject-specific essays and exam essays. Use markschemes and tutor feedback to build up a frame that works for you and helps you always include the right things...

Structure

To be able to write a really good essay or assignment, you need to learn which structure you should be following. Again, this may be slightly different for each subject, so make sure you check with your teachers before you start your essay writing. Ask for a basic structure outline, or some specimen examples of good essays, so that you know what you should be including and how you should lay your work out.

break

A standard essay structure would be built from the following components:

break

break

You might also be expected to include a Bibliography at the end, particularly if it is a coursework assignment.

break

We will now break each section down, so you know what you should be aiming to include...

The Introduction

Arguably, this one of the hardest parts of an essay to write. The conclusion can be tough, but at least by then you already have lots written down. But the introduction starts with a blank piece of paper, and it's always difficult to be sure how to begin...

Arguably, this one of the hardest parts of an essay to write. The conclusion can be tough, but at least by then you already have lots written down. But the introduction starts with a blank piece of paper, and it's always difficult to be sure how to begin...

break

The introduction should Explain to the reader exactly what your essay will be about. Imagine the first part of a lesson, or a presentation - the bit where you are briefly told what's coming up so you know you're definitely in the right room! Essays need the same thing.

An introduction should set the context of the essay, be relevant and to the point. Length may vary, but it should typically be around 7-10% of the total length of your essay. So if your essay is about 1,500 words, your introduction should be just over 100 words, and possibly not much more than 150.

break

It should:

- state exactly what the essay is about.

break

This is actually very easy to do! Just look at the question (and your break down of the question in your plan) and reword it.

break

For example: "This essay will argue that the character of Hamlet, from Shakespeare's play of the same name, was not mad."

break - define any key words or phrases to show that you understand what is meant by them, and to set the parameters for your upcoming argument.

break

For instance: "In this essay, the term 'mad' will refer to insanity, rather than a state of anger."

break

If you have used BUG to help you break down your question, you should already know which terms to define in your essay - they'll be underlined!

break

Tip: If in doubt, define everything! This might sound crazy, but you'd be surprised what knowledge examiners are looking for. (I once saw a mark scheme that expected students to define 'United Kingdom', even though you would have thought the definition was obvious... But is it...? Better to prove you know than leave doubt...!)

break - include a brief list of your planned arguments.

break

Again, think back to a good class or a clear presentation - you'll normally have the day's topic broken down into chunks so you know what will be covered or discussed. However, it is just a quick overview, with no details yet. They come later.

break

An example might be: "It can be argued that Hamlet is not mad because of three main reasons - his initial delusion (talking to his father's ghost) is not considered mad by his friends, he is clearly able to express his thoughts and feelings, and he makes a conscious decision to be perceived as mad."

break

The above example introduction is so far only around 86 words long, but I would also add a short introduction to the play as well: "Hamlet, written by William Shakespeare some time around 1600, is the story of the Prince of Denmark, Hamlet, and his tragic quest to avenge his father's murder..." etc.). Again, this is just briefly setting the context and proving that I do know the subject matter that I'm about to evaluate. I'm not telling the whole story, or yet discussing the points of the play I'll be analysing later. Sometimes the definitions will cover this context without you needing to add anything more.

break

Some top tips if you're struggling to start an introduction are:

- Use standard phrases in your first draft, such as:

break

"This essay will argue...",

"[X] can be defined as...",

"The arguments used in this essay will be...".

break

This moves you away from blank-page-panic and helps you to remember the main elements that should be included in an introduction. You can reword sentences later if you need to.

break - Reword the essay question as your opening line. This helps you to focus on the actual question being asked (rather than the one you might want to be answering!).

break - Use the BUG breakdown from your plan to help you know exactly what to define.

break - Do not start writing your arguments within the introduction! This is a common mistake and often an attempt at padding the introduction. Sum up what you arguments will be, but do not go into any more detail than that at this stage. The detail comes later...

break

Once you've drafted your introduction, ask yourself:

- "Have I introduced the question being asked?" Re-read the question and then your introduction to make sure.

BREAK and - "If the person reading this knows absolutely nothing about this topic, have I explained enough for them to be able to understand what's coming up in my main argument?" You have to stop thinking that you're writing for a teacher or an examiner who already knows everything, and imagine you're writing for people who have no clue. That's your best chance of writing a clear and detailed essay.

break

Quick Activity

Quick Activity

Before you move on, have a go at analysing some sample introductions to see if you can spot the good from the not so good. This is an essential activity and worth having a quick go at before you move on. Complete the worksheet and, if you wish, you can upload it below.

| Sample Introductions Worksheet | Upload your completed worksheet here |

The Main Arguments (Middle)

For most students, this is the easy bit - you just write down everything you know, right?

For most students, this is the easy bit - you just write down everything you know, right?

Wrong. That's often where all those less than positive comments we covered at the start about lack of structure, etc. come from.

However, the middle is definitely the easier and more interesting bit of any essay or assignment.

BREAK

When it comes to the middle, you must stick to your plan. You have chosen the 3 - 5 main points to focus on to prove your argument and they are the only ones you will use, so don't get distracted! And don't feel the need to add one extra point the end, just in passing, to prove you know that too! Pick the best arguments and stick to them. If another pops into your head as you write and it's better than one of your original choices, then make a substitution - note it on your plan first and find the evidence, then use it.

As mentioned before, you need to check with your subject teachers as to what, exactly, you need to include in the main arguments of your essay, but as a general rule you should be following the amusingly named P E E system. You may remember this from GCSE, when it stood for Point, Evidence, Explanation? At A level it stands for:

break

Point - the main arguments you chose in your plan are your points. Standard phrases might include: "One argument for... is...", or "An argument for the case that... is..."

Example or Evidence - you need to find this in your text books or from other credible sources; do not be tempted to make this up or use your own experience/opinion unless the essay specifically asks you to do this. At A level you should be researching answers and using provable evidence. Standard phrases here might include: "This can be shown/seen in/when..." or "An example of this is..." You can also link in quotes or statistics at this point.

Evaluation - how does your evidence prove your point? What does it show that backs up your point? why is it relevant to your point? Etc. The key word here is "because", and you should keep asking yourself how and why to really break down how and why the evidence backs up your point and answers the original question.

Some of you may have used P E E L at school, with the L standing for Link, i.e. link back to the original question. You should always re-read the original question whenever you finish making an argument to be sure it definitely links and, if necessary, don't be afraid to keep using the words from the question to make sure you points clearly link.

break

As well as analysing the evidence that backs up your point, you may also need to increase your evaluation by providing counterarguments that strengthen your points. It's a good idea to plan these beforehand as well. I like to use the mnemonic C-A R to help me remember this process:

break

Counter-Argument - come up with an exact counter point to the main point you have just made. You can use standard phrases such as "It could be argued that..." to help you start this. For example, if I wanted to argue against Hamlet being sane in his reasoning, I could say:

"It could be argued that, although Hamlet is capable of clearly expressing his thoughts and feelings, much of this is done in soliloquies (to an invisible audience) and therefore might be as seen as Hamlet talking to himself, which could be seen as a sign of madness..."

Return (to original point) - whenever you counter-argue, your counter-argument should hopefully be weaker than your main point (otherwise your conclusion will be flawed).

I cannot argue that Hamlet is not mad based on my three main points if the counter-arguments make more sense and have better evidence! In that case, I would need to change my conclusion and start all over again. (If this ever happens to you, don't worry - it's a good thing as it will teach you to look carefully at the evidence before making your case in future...)

Again, you can use standard phrases to help you return to your main point, such as "However", "Nevertheless", etc.

"However, the soliloquy is a dramatic device used by characters that are not considered mad, so it is not in itself strong enough evidence to suggest that Hamlet is doing it because he is mad..."

break

You should be able to repeat this for each of your arguments (so 3 - 5 times), and tick them off your plan as you complete them.

You should be able to repeat this for each of your arguments (so 3 - 5 times), and tick them off your plan as you complete them.

break

Each argument should receive the same amount of effort and time, and therefore approximately the same amount of words - but don't force yourself to use the exact same amount! The best indicator is the length of the paragraphs - do they all look roughly the same length? If one is much shorter, or much longer, why is this? Often the first point ends up being quite long in the first draft, so make sure to read through it carefully and decide if it really needs to be that long. If it does, then what are your other points missing that you need to add in to make them that long too? If it doesn't, what can you cut?

For a 1,500 word essay, at least 1,000 of the words should be in the middle, so you may need to give around 300-350 words per argument to a three-point essay.

break

Some subjects will require you to include evaluation of methodology (such as in Sociology or Psychology) or of sources (such as History courses). You may need to make sure to reference particular names, dates or concepts (e.g. government intervention vs. private business). You should find out what these are and try making your own mnemonics to help you meet the essay requirements each time.

At the end of this course you will find a template to help you lay out an essay. You can amend this to include all those elements you need to make sure you cover everything required of a subject essay.

The Conclusion

Finally, we've reached the end, the conclusion... the second hardest part of any essay.

Finally, we've reached the end, the conclusion... the second hardest part of any essay.

You might be feeling pretty good about everything you've written so far, but that tricky conclusion can ruin everything and send you right back to writer's block.

One of the most common student questions is "how do I write a conclusion without just repeating what I've already written?" Fear of repeating points is often the reason students suddenly start writing about something completely different in their conclusions, entirely confusing the reader! Where did that come from...?

break

A conclusion summarises your main ideas - so there will be an element of repetition, and it's best not to be afraid of this. Think again of a good lesson or presentation. At the end, there will be a quick summary of what you've covered during the session, just to remind you and similar to the introduction, but it will probably now include a few notes on how you learnt or discussed the topics. That's what you're looking to do for an essay conclusion - summarise your arguments and bring everything together...

break

How to write the conclusion

break

- To start with, go back to the original question in your plan and answer it. If you've followed your plan (and your arguments throughout the essay have been strong enough), then the answer should still be exactly the same as your tentative answer in the plan. (If it's not, you may need to redraft...)

break

Example: "In conclusion, the evidence in this essay has shown that Hamlet is arguably not mad, but just pretending to be in order to hide his anger and grief and disguise his attempts at revenge."

break

It is a good idea to clearly mark your conclusion with a standard phrase such as "in conclusion", "to sum up", "to conclude", etc. This is particularly the case when writing exam essays or coursework assignments, as you will often be allocated specific marks for your conclusion; it is therefore very helpful if the examiner or moderator can clearly see that you have started your conclusion.

break - Now you need to sum up how you came to that conclusion, constantly linking your points back to the question. Go back to your introduction, where you listed the arguments you were going to use, and list them again, but this time with qualifying statements, possibly recognising any counter-arguments as well. I've used bold text just for the example below so that you can see my original three points:

break

Example: "This has been shown through examining Hamlet's interaction with his father's ghost, which might have been taken as a delusion were it not for the fact it was a shared experience with other members of the castle. It can also be concluded that Hamlet is not mad from his ability to clearly express his thoughts and feelings and, despite often doing this in soliloquies, he does not show himself to be erratic or disengaged from the process as other 'mad' characters have appeared in Shakespeare's plays, such as Ophelia. Finally, the fact that Hamlet clearly expresses his intention to pretend to be mad is a good indicator that he probably isn't, although the decision could lead him to madness later as a self-fulfilling prophecy..."

break - You can also use the conclusion to suggest other questions which might arise from the essay or might need further research, if it's relevant. This can help to finish off your conclusion, or point out your arguments, although strong, are still not definitive.

break

Example: "Ultimately, it could be argued that whether or not Hamlet is mad really comes down to how he is portrayed by the actor or perceived by the audience, but the evidence from Shakespeare's text, as evaluated in this essay, would suggest that Hamlet is not mad."

break

Unless you're specifically asked to argue 'For AND Against' a question, it's a good idea to practice writing one-sided conclusions. Lots of students worry that they need to sit on the fence when it comes to a conclusion - "you could argue this, but you could also argue that, and I'm not sure I can state which one's better as they both make great points..." Don't be afraid to be brave and pick one side of an argument - as long as it is answering the question correctly, your arguments throughout your essay are strong, and they're backed up with evidence, it shouldn't be wrong to make that final decision. You can (and should) always acknowledge counter-arguments, but they will hopefully not be as strong as your chosen side.

Unless you're specifically asked to argue 'For AND Against' a question, it's a good idea to practice writing one-sided conclusions. Lots of students worry that they need to sit on the fence when it comes to a conclusion - "you could argue this, but you could also argue that, and I'm not sure I can state which one's better as they both make great points..." Don't be afraid to be brave and pick one side of an argument - as long as it is answering the question correctly, your arguments throughout your essay are strong, and they're backed up with evidence, it shouldn't be wrong to make that final decision. You can (and should) always acknowledge counter-arguments, but they will hopefully not be as strong as your chosen side.

Also, don't be afraid to come to the opposite conclusion to that implied in the question. For instance: "'The government should stop trying to control our lives.' Discuss." A lot of students would be tempted to instantly agree with the question's conclusion ("yes they should") because the wording seems to point in that direction, but if you can easily prove the statement wrong ("no, they shouldn't!") then do!

break

My example conclusion on Hamlet above is now about 200 words long which, for an essay of 1,500 words, is pretty good. You should be aiming for your conclusion to be between 12-15% of you overall essay length, so a 1,500 word essay might use approximately 180 - 225 words for that final paragraph.

break

So, to sum up:

- Make your conclusion clear to the reader.

- Restate your original answer.

- Restate your original points, but this time with summarised qualifying statements.

- Always link back to the essay question to finish.

break

As with every other section in this course, don't forget to check with your subject teachers in case there are any specific elements you need to add to their subject's conclusions.

break

Quick Activity

Quick Activity

As with the example introductions, you should now take a look at some sample conclusions on this worksheet, using the same essay question as before, and again give your feedback on what is good or bad about them. This is an essential activity, so you can upload your answers belowif you wish.

| Sample Conclusions Worksheet | Upload your completed worksheet here |

Layout and Language

Whether you are handwriting or typing your essay, it's important to give some thought to the layout of your text on the page. No one likes to see huge clumps of writing with no breaks and lots of long sentences they need to wade through!

Whether you are handwriting or typing your essay, it's important to give some thought to the layout of your text on the page. No one likes to see huge clumps of writing with no breaks and lots of long sentences they need to wade through!

break

If you have a good grasp of the subject material, then you should be able to write your essay answer with clarity and coherence.

Use short sentences, ideally interspersed with longer sentences to produce a more polished style and flow.

Leave a margin between the edge of the page and your writing so that teachers can include feedback, and so that your writing isn't unnaturally and thinly stretched across the page.

Leave lines between paragraphs.

Take a look at text books and academic journals to see how text is laid out and sentence structure is used in formal writing. This is a good way to learn and compare appropriate layout.

break

If you have made a good plan, then you should also have very little problem with layout as you can use the plan to give you an idea of how to break up your paragraphs. For a 1,500 word essay, you might break it down as:

break

break

Introduction - 1 paragraph

Point 1 - 1 paragraph.

Point 2 - 1 paragraph.

Point 3 - 1 paragraph.

Conclusion - 1 paragraph

break

This is a nice, five-paragraph essay layout which is evenly split between its points. If your essay is more than 1,500 words, you will just be adding extra Point paragraphs between the introduction and conclusion. For a longer coursework assignment, you may want to split points from counter-arguments, but make sure you link the counter-argument back to the original point before moving on. Ideally, your paragraphs should flow into each other.

breaker

Language

Language

It's better to use simple and straightforward language, although you should, of course, be using formal written language, rather than a spoken or colloquial (slang) style of language; for instance, do not use '&' instead of 'and'!

Try to avoid contractions in your own writing such as "can't" or "don't", instead using the full versions ("cannot", "do not"), although if you are including a quote, you do not need to change someone else's words - just make sure you use quotation marks [" "].

Avoid using personal pronouns, such as 'I', 'you or 'we'. Unless the essay specifically asks for your opinions, you should not be giving or even implying them (e.g. "I believe Hamlet is not mad..."). Likewise, avoid addressing the reader as if you understand or know what they know (e.g. "You can clearly see that Hamlet is not mad."), and don't include them with you in suggesting that you all agree with each other (e.g. "We can see that Hamlet is not mad"). A few typical examples with some suggested alternatives would be:

| Avoid | Possible alternative... |

| I will make the argument that Hamlet is mad. | This essay will argue that Hamlet is mad. |

| In my opinion, Hamlet is mad because... | It could be argued that Hamlet is mad because... |

| You can clearly see here that Hamlet is mad. | This evidence clearly shows that Hamlet is mad. |

| We can see from this that Hamlet is probably mad. | It is therefore possible to conclude that Hamlet is mad. |

break

Try to avoid starting sentences with coordinating conjunctions, such as "and", "but", so" and "or". If possible, connect sentences that start with these words to the previous sentence or, if the sentence is getting too long, try replacing them with the following:

"And" = "Additionally" or "Moreover" (you can use these instead of "Also" as well)

"But" = "Nevertheless" or "However"

"So" = "therefore" or "thus"

"Or" = "Alternatively", "Instead", "Otherwise", or "On the other hand"

break

Make sure you are using the right punctuation. Use full stops and commas appropriately - commas create short pauses within sentences, while full stops finish the sentence. Always make sure you use capital letters at the start of sentences and for the start of any proper nouns (names of people, places or organisations). If you're not sure how to use semi-colons, then don't use them! Make sure you do include a question mark [?] after a question.

Use scientific and technical words appropriately - again read your text books, academic journals, or just use a dictionary to check your understanding.

Reviewing and Proofreading

Once you've finished the first draft of your essay, it's important not to assume it's all over, finished, ready to hand in. A big mistake many students make (and which leads to lower grades) is not to bother reviewing and proofreading. This is why you should never leave essay writing until the night before the hand-in date.

break

Drafting Tips

Drafting Tips

A little tip for essay drafting is to use the computer for your first draft - even if you will need to handwrite your final version. Using a computer means you can edit your work much more easily, moving sentences and paragraphs around, and cutting down the word count with a visible counter.

You can also use Read & Write Gold to help proofread your work before you create your final piece.

Once you have your final draft on the screen, you can either print this out, or pull out your note paper and start writing it out.

A lot of students who need to handwrite their essays only ever create one draft and usually hand this in as a final piece - this is fine for a bit of timed practice, but is no good for coursework assignments or formal essays. You need to draft and re-draft to get things right.

break

Reviewing Checklist

Reviewing Checklist

Here's a review checklist which might be useful for you to make sure that you have gone through all the necessary processes in the preparation of your essay. As you read through your draft, answer the following questions:

-

- Have I answered the particular question that was set?

break - Have I divided up the question into separate smaller questions and answered these?

break - Have I covered all the main aspects?

break - Have I covered those in enough depth?

break - Is the content relevant?

break - Is the content accurate?

break - Have I arranged the material logically?

break - Does the essay move smoothly from one section to the next, from paragraph to paragraph?

break - Is each main point supported by examples and evaluation?

break - Have I acknowledged all sources and references?

break - Have I distinguished clearly between my own ideas and those of others?

break - Is the essay the right length?

break - Have I written plainly and simply, using formal and appropriate language and terminology?

break - Have I read it aloud (or had it read aloud) at least once to sort out clumsy and muddled phrasing?

break - Are the grammar, punctuation and spelling acceptable?

break - Is the essay neatly and legibly written (if handwritten), or neatly laid out (if typed)?

break - Have I presented a convincing case which I could justify in a discussion?

- Have I answered the particular question that was set?

break

Proofreading Tips

No matter how carefully we examine a text, it seems there's always one more little mistake waiting to be discovered. There's no fool-proof formula for perfect proofreading every time. It's just too tempting to see what we meant to write rather than the words that actually appear on the page or screen. But these tips should help you see (or hear) your errors before anybody else does.

break

Give it a rest.

If time allows, set your text aside for a few hours (or days) after you've finished your first draft, and then proofread it with fresh eyes. Rather than remember the perfect paper you meant to write, you're more likely to see what you've actually written.

break

Look for one type of problem at a time.

Read through your text several times, concentrating first on sentence structures, then word choice, then spelling, and finally punctuation. As the saying goes, if you look for trouble, you're likely to find it.

break

Double-check facts, figures, and proper names.

In addition to reviewing for correct spelling and usage, make sure that all the information in your text is accurate.

break

Review a hard copy.

Print out your text and review it line by line: rereading your work in a different format may help you catch errors that you previously missed.

break

Read your text aloud.

Or better yet, use Read & Write Gold, or ask a friend or colleague to read it aloud. You may hear a problem (a faulty verb ending, for example, or a missing word) that you haven't been able to see.

break

Use a spellchecker, but carefully.

The Microsoft (or Apple) spellchecker can help you catch repeated words, reversed letters, and many other common errors - but it's certainly not fool-proof. If you’re not sure, you can also try the spellcheck on Read & Write Gold, which provides dictionary definitions alongside spellings, helping you to pick the correct word.

Trust in a dictionary. Your spellchecker can tell you only if a word is a word, not if it's the right word. For instance, if you're not sure whether sand is in a desert or a dessert, use a dictionary (or try this Glossary of Commonly Confused Words).

break

Read your text backward.

Another way to catch spelling errors is to read backward, from right to left, starting with the last word in your text. Doing this will help you focus on individual words rather than sentences.

break

Create your own proofreading checklist.

Keep a list of the types of mistakes you commonly make, and then refer to that list each time you proofread.

break

Ask for help.

Invite someone else to proofread your text after you have reviewed it. A new set of eyes may immediately spot errors that you've overlooked.

break

break

The Review Checklist was adapted from Godalming College L6 Core Studies Tutorial Programme, Student Guide, 2007-8

The Proofreading Tips were adapted from http://grammar.about.com/od/improveyourwriting/a/tipsproofreading.htm

Feedback

Another aspect of essay writing which is often overlooked is that of acknowledging feedback. You hand in an essay, completing your half of the agreement, and your teacher returns it to with a grade and notes justifying that grade. Job done?

Another aspect of essay writing which is often overlooked is that of acknowledging feedback. You hand in an essay, completing your half of the agreement, and your teacher returns it to with a grade and notes justifying that grade. Job done?

It's easy just to see the grade and ignore everything else - after all, the essay is written, you'll never have to do it again, so why should you care what you did well and what you need to improve on, as long as the grade is ok...?

Teachers don't spend their time writing feedback for fun - it is one of the most important parts of their job and a key element of their teaching and your learning. Feedback is designed to improve your skills, knowledge and grades.

break

Actively using feedback

Feedback should be read through carefully. Set some specific time aside to do this, as soon as possible after receiving your essay back. If there's anything you don't understand or you need clarified, ask your teacher about is as soon as possible, as that way it is still likely to be fresh in their mind, and you won't forget to ask later.

You should then make your own version of the notes your teacher provided and keep them in your subject file - you might write them on a separate piece of paper, or underneath the essay itself if there's room. You can sum up the feedback by answering the following questions:

- What did I do well in this essay/assignment?

- What did I need to improve on in this essay/assignment? (Content and Layout problems)

- What should I make sure I improve on in my next essay?

Alternatively you could use this checklist, ticking next to the relevant core criteria, to quickly record your feedback. You may want to adapt the checklist for the specific marking criteria for your subject. Don't forget to use the 'other comments' section to summarise what you will improve on for next time and which knowledge areas you need to work on.

Before you start your next essay, quickly read back over your noted feedback, in whatever format you've used, to remind you what you need to do to improve your grade this time.

break

Be Receptive to criticism - good and bad

Be Receptive to criticism - good and bad

The kind of feedback you receive on assignments will vary greatly, depending on the subject area, the type of assignment and your tutor.

Sometimes it may feel difficult experience to read comments and criticisms of your on a particular piece, especially when you thought you had performed well with the question but the feedback still appears to suggest more improvement is needed. It is easy to take such comments personally, as though you are being told what you have written is no good rather than acknowledging the effort you made.

Feedback on your writing, however, needs to be looked at as a valuable aid to skills development. You need to try and take a step back from your essays and assignments (as well as presentations, practicals, orals, etc.), and look at them as a series of exercises, each of which will result in important feedback.

Even if you do not receive feedback on your essay until after an examination (for instance, comparing your exam work or grade to a mark scheme after it is released, or receiving feedback on a mock), you can still use it to help you develop your skills (all of which will be beneficial to your future studies).

So do make sure that you read and reflect upon your feedback, and learn from it. Having direct and detailed comments on your essays and assignments can be a great opportunity to enhance your skills and knowledge.

break

Here are a few more tips to help you deal with and use the feedback you receive:

- Know what your grade or percentage mark means. Sometimes you might be getting As all the time in one subject, but Cs and Ds in another. This is because different subjects have different requirements and marking schemes. As well as your grade, find out what the grade boundaries and Assessment Objectives (AOs) are. If your teacher hasn't provided you with these yet, you can look up a past mark scheme on your subject's Exam Board website and check what the examiners are given as an indication of grade. Compare your grade and its requirements to the highest band and see if there's anything you could improve on.

break - Don't just look at the back of your essay for comments, as teachers often make comments throughout essay.The amount of feedback you receive will vary depending on subject area and tutor. The comments may seem familiar to you - such as "you need to clarify this point" or "this essay lacks structure". You need to ensure, however, that you can make sense of these comments and that you know how to improve in this areas. If you're not sure, ask.

break - Be aware that feedback often covers both the content of the essay or assignment and the way you have written it. The comments on content tend

to be more specific to the subject area, and can be very useful when it comes to preparing for your next essay in that subject, or when revising for the exam. Make sure you do spend some time following up an knowledge gaps when you write up your own feedback notes. Other comments often refer to aspects of your writing, and could include your argument, structure, clarity of expression and referencing. Have a look at the feedback you have received on one of your essays or assignments and make sure you can identify which comments deal with content which deal with general writing issues.

to be more specific to the subject area, and can be very useful when it comes to preparing for your next essay in that subject, or when revising for the exam. Make sure you do spend some time following up an knowledge gaps when you write up your own feedback notes. Other comments often refer to aspects of your writing, and could include your argument, structure, clarity of expression and referencing. Have a look at the feedback you have received on one of your essays or assignments and make sure you can identify which comments deal with content which deal with general writing issues.

break - Talk to your fellow students. Some students may feel uncomfortable with discussing their marks and comments. But it does help to compare, contrast and discuss any comments you may have received with other students on your course. It is not always easy to fully understand what the teacher may have meant by their comments. By talking it over with other students familiar with the subject, you may gain further insight into your essay/assignment and your feedback. It is also a good idea, if your classmates are willing, to read someone else's essay, particularly if they received a better grade or better feedback than you. Is it clear why? Can you take any tips from that student's work and apply them to your own?

break

So, in short: read all your feedback, re-write your feedback and review it before writing your next essay, question your feedback if you do not understand it, and - most importantly - do not be disheartened or to give up after a bad grade or negative feedback; just use it to write a far better essay next time!

break

break

'Be Receptive' content adapted http://www.humanities.manchester.ac.uk/studyskills/progress/feedback/feedback_how_to.html (from material by Dr. Alyssa Phillips, Combined Studies, University of Manchester)

Summary and Review Quiz

Hopefully this course has shown you:

Hopefully this course has shown you:

break

- why essays are an important part of your courses,

break - how planning helps you to focus your essay and achieve better grades,

break - how to easily structure and clearly layout an essay,

break - what to use to help draft, review and proofread your work before handing it in, and

break - how to actively use feedback to continue to improve your essay and assignment writing.

break

You should now be able to face your next essay or assignment with a positive plan of action and a confident sense that you can do really well. Gone are the days of the blank-page-panic at 2am in the morning on the day your essay is due in! Now you can rush home the minute you're set a question and get started, using all the tips and skills you've learnt, safe in the knowledge you'll be finished with your first draft by teatime... Probably...

break

Review Quiz

Review Quiz

Now that you've worked through this course, complete the Review Quiz below.

| Writing Essays & Assignments Review Quiz |

Well done for finishing the course - enjoy your future essay writing...!

BREAK

ANSWERS

In case you were interested, some suggested answers to the example introductions and conclusions worksheets you completed earlier can be found here (but please don't cheat!):

BREAK

BREAK

________________________________________________________________________________________

Further suggested reading and support:

BREAK

|

If you would like to continue learning about assignment writing, take a look at The Open University's Preparing Assignments study booklet, which includes sections on oral assignments, short-answer assignments, writing paragrphs, linking words, paraphrasing, quoting and referencing, and improving your written English. |